To the House of Representatives:

I return to the House of Representatives, in. which it originated, the bill entitled "An act making appropriations to pay fees of United States marshals and their general deputies," with the following objections to its becoming a law:

The bill appropriates the sum of $600,000 for the payment during the fiscal year ending June 30, 1880, of United States marshals and their general deputies. The offices thus provided for are essential to the faithful execution of the laws. They were created and their powers and duties defined by Congress at its first session after the adoption of the Constitution in the judiciary act which was approved September 24, 1789. Their general duties, as defined in the act which originally established them, were substantially the same as those prescribed in the statutes now in force.

The principal provision on the subject in the Revised Statutes is as follows:

Sec. 787. It shall be the duty of the marshal of each district to attend the district and circuit courts when sitting therein, and to execute throughout the district all lawful precepts directed to hint and issued under the authority of the United States; and he shall have power to command all necessary assistance in the execution of his duty.

The original act was amended February 28, 1795, and the amendment is now found in the Revised Statutes in the following form:

SEC. 788. The marshals and their deputies shall have in each State the same powers in executing the laws of the United States as the sheriffs and their deputies in such State may have by law in executing the laws thereof.

By subsequent statutes additional duties have been from time to time imposed upon the marshals and their deputies, the due and regular performance of which are required for the efficiency of almost every branch of the public service. Without these officers there would be no means of executing the warrants, decrees, or other process of the courts, and the judicial system of the country would be fatally defective. The criminal jurisdiction of the courts of the United States is very extensive. The crimes committed within the maritime jurisdiction of the United States are all cognizable only in the courts of the United States. Crimes against public justice; crimes against the operations of the Government, such as forging or counterfeiting the money or securities of the United States; crimes against the postal laws; offenses against the elective franchise, against the civil rights of citizens, against the existence of the Government: crimes against the internal-revenue laws, the customs laws, the neutrality laws; crimes against laws for the protection of Indians and of the public lands--all of these crimes and many others can be punished only under United States laws, laws which, taken together, constitute a body of jurisprudence which is vital to the welfare of the whole country, and which can be enforced only by means of the marshals and deputy marshals of the United States. In the District of Columbia all of the process of the courts is executed by the officers in question. In short, the execution of the criminal laws of the United States, the service of all civil process in cases in which the United States is a party, and the execution of the revenue laws, the neutrality laws, and many other laws of large importance depend on the maintenance of the marshals and their deputies. They are in effect the only police of the United States Government. Officers with corresponding powers and duties are found in every State of the Union and in every country which has a jurisprudence which is worthy of the name. To deprive the National Government of these officers would be as disastrous to society as to abolish the sheriffs, constables, and police officers in the several States. It would be a denial to the United States of the right to execute its laws--a denial of all authority which requires the use of civil force. The law entitles these officers to be paid. The funds needed for the purpose have been collected from the people and are now in the Treasury. No objection is, therefore, made to that part of the bill before me which appropriates money for the support of the marshals and deputy marshals of the United States.

The bill contains, however, other provisions which are identical in tenor and effect with the second section of the bill entitled "An act making appropriations for certain judicial expenses," which on the 23d of the present month was returned to the House of Representatives with my objections to its approval. The provisions referred to are as follows:

Sec. 2. That the sums appropriated in this act for the persons and public service embraced in its provisions are in full for such persons and public service for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1880; and no Department or officer of the Government shall during said fiscal year make any contract or incur any liability for the future payment of money under any of the provisions of title 26 mentioned in section 1 of this act until an appropriation sufficient to meet such contract or pay such liability shall have first been made by law.

Upon a reconsideration in the House of Representatives of the bill which contained these provisions it lacked a constitutional majority, and therefore failed to become a law. In order to secure its enactment, the same measure is again presented for my approval, coupled in the bill before me with appropriations for the support of marshals and their deputies during the next fiscal year. The object, manifestly, is to place before the Executive this alternative: Either to allow necessary functions of the public service to be crippled or suspended for want of the appropriations required to keep them in operation, or to approve legislation which in official communications to Congress he has declared would be a violation of his constitutional duty. Thus in this bill the principle is clearly embodied that by virtue of the provision of the Constitution which requires that "all bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives" a bare majority of the House of Representatives has the right to withhold appropriations for the support of the Government unless the Executive consents to approve any legislation which may be attached to appropriation bills. I respectfully refer to the communications on this subject which I have sent to Congress during its present session for a statement of the grounds of my conclusions, and desire here merely to repeat that in my judgment to establish the principle of this bill is to make a radical, dangerous, and unconstitutional change in the character of our institutions.

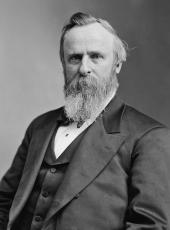

RUTHERFORD B. HAYES

Rutherford B. Hayes, Veto Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/203762