To the Senate:

I return without approval Senate bill No. 1547, entitled "An act granting a pension to Mary Ann Dougherty."

A large share of the report of the Senate committee to which this bill was referred, and which report is adopted by the committee of the House, as is usual in such cases, consists of a petition signed by Mary Ann Dougherty, addressed to the Congress, in which she states that she resides in Washington, having removed here with her husband in 1863 from New Jersey; that shortly after their arrival in this city her husband, Daniel Dougherty, returned to New Jersey and enlisted in the Thirty-fourth Regiment New Jersey Volunteers; that she obtained employment in the United States arsenal making cartridges, and that while so engaged she was injured by an explosion.

She also states that she had a young son killed by machinery in the navy-yard, and that at the grand review of the Army after the close of the war another son, 6 years old, was stolen by an officer of the Army and has not been heard of since. She further says that her husband left his home in 1865 and has not been heard of since, and that she believes he deserted her on account of her infirmities.

It is alleged in the report that she received a pension as the widow of Daniel Dougherty until it was discovered that he was alive, when her name was dropped from the rolls.

The petition of this woman is indorsed by the Admiral and several other officers of the Navy and a distinguished clergyman of Washington, certifying that they know Mrs. Dougherty and believe the facts stated to be true.

There is no pretense made now that this beneficiary is a widow, though she at one time claimed to be, and was allowed a pension on that allegation. Her present claim rests entirely upon injuries received by her when she was concededly not employed in the military service. If the pension now proposed is allowed her, it will be a mere act of charity.

Her husband, Daniel Dougherty, is now living in Philadelphia, and is a pensioner in his own right for disability alleged to have been incurred while serving in the Thirty-fourth New Jersey Volunteers. Of this fact this beneficiary has been repeatedly informed; and yet she states in her petition that her husband deserted her in 1865 and has not been heard of since.

It is alleged in the Pension Bureau that in 1878 she succeeded in securing a pension as the widow of Daniel Dougherty through fraudulent testimony and much false swearing on her part.

The police records of the precinct in which she has lived four years show that she is a woman of very bad character, and that she has been under arrest nine times for drunkenness, larceny, creating disturbance, and misdemeanors of that sort.

It happens that this claimant, by reason of her residence here, has been easily traced and her character and untruthfulness discovered. But there is much reason to fear that this case will find its parallel in many that have reached a successful conclusion.

I can not spell out any principle upon which the bounty of the Government is bestowed through the instrumentality of the flood of private pension bills that reach me. The theory seems to have been adopted that no man who served in the Army can be the subject of death or impaired health except they are chargeable to his service. Medical theories are set at naught and the most startling relation is claimed between alleged incidents of military service and disability or death. Fatal apoplexy is admitted as the result of quite insignificant wounds, heart disease is attributed to chronic diarrhea, consumption to hernia, and suicide is traced to army service in a wonderfully devious and curious way.

Adjudications of the Pension Bureau are overruled in the most peremptory fashion by these special acts of Congress, since nearly all the beneficiaries named in these bills have unsuccessfully applied to that Bureau for relief.

This course of special legislation operates very unfairly.

Those with certain influence or friends to push their claims procure pensions, and those who have neither friends nor influence must be content with their fate under general laws. It operates unfairly by increasing in numerous instances the pensions of those already on the rolls, while many other more deserving cases, from the lack of fortunate advocacy, are obliged to be content with the sum provided by general laws.

The apprehension may well be entertained that the freedom with which these private pension bills are passed furnishes an inducement to fraud and imposition, while it certainly teaches the vicious lesson to our people that the Treasury of the National Government invites the approach of private need.

None of us should be in the least wanting in regard for the veteran soldier, and I will yield to no man in a desire to see those who defended the Government when it needed defenders liberally treated. Unfriendliness to our veterans is a charge easily and sometimes dishonestly made.

I insist that the true soldier is a good citizen, and that he will be satisfied with generous, fair, and equal consideration for those who are worthily entitled to help.

I have considered the pension list of the Republic a roll of honor, bearing names inscribed by national gratitude, and not by improvident and indiscriminate almsgiving.

I have conceived the prevention of the complete discredit which must ensue from the unreasonable, unfair, and reckless granting of pensions by special acts to be the best service I can render our veterans.

In the discharge of what has seemed to me my duty as related to legislation, and in the interest of all the veterans of the Union Army, I have attempted to stem the tide of improvident pension enactments, though I confess to a full share of responsibility for some of these laws that should not have been passed.

I am far from denying that there are cases of merit which can not be reached except by special enactment, but I do not believe there is a member of either House of Congress who will not admit that this kind of legislation has been carried too far.

I have now before me more than 100 special pension bills, which can hardly be examined within the time allowed for that purpose.

My aim has been at all times, in dealing with bills of this character, to give the applicant for a pension the benefit of any doubt that might arise, and which balanced the propriety of granting a pension if there seemed any just foundation for the application; but when it seemed entirely outside of every rule in its nature or the proof supporting it, I have supposed I only did my duty in interposing an objection.

It seems to me that it would be well if our general pension laws should be revised with a view of meeting every meritorious case that can arise. Our experience and knowledge of any existing deficiencies ought to make the enactment of a complete pension code possible.

In the absence of such a revision, and if pensions are to be granted upon equitable grounds and without regard to general laws, the present methods would be greatly improved by the establishment of some tribunal to examine the facts in every case and determine upon the merits of the application.

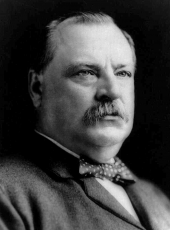

GROVER CLEVELAND

Grover Cleveland, Veto Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/205040