To the House of Representatives:

I return without approval House bill No. 1406, entitled "An act to provide for the sale of certain New York Indian lands in Kansas."

Prior to the year 1838 a number of bands and tribes of New York Indians had obtained 500,000 acres of land in the State of Wisconsin, upon which they proposed to reside. In the year above named a treaty was entered into between the United States and these Indians whereby they relinquished to the Government these Wisconsin lands. In consideration thereof, and, as the treaty declares," in order to manifest the deep interest of the United States in the future peace and prosperity of the New York Indians," it was agreed there should be set apart as a permanent home for all the New York Indians then residing in the State of New York, or in Wisconsin, or elsewhere in the United States, who had no permanent home, a tract of land amounting to 1,824,000 acres, directly west of the State of Missouri, and now included in the State of Kansas--being 320 acres for each Indian, as their number was then computed--" to have and to hold the same in fee simple to the said tribes or nations of Indians by patent from the President of the United States."

Full power and authority was also giver to said Indians "to divide said lands among the different tribes, nations, or bands in severally," with the right to sell and convey to and from each other under such rules and regulations as should be adopted by said Indians in their respective tribes or in general council.

The treaty further provided that such of the tribes of these Indians as did not accept said treaty and agree to remove to the country set apart for their new homes within five years or such other time as the President might from time to time appoint should forfeit all interest in the land so set apart to the United States; and the Government guaranteed to protect and defend them in the peaceable possession and enjoyment of their new homes.

I have no positive information that any considerable number of these Indians removed to the lands provided for them within the five years limited by the treaty. Their omission to do so may have been owing to the failure of the Government to appropriate the money to pay the expense of such removal, as it agreed to do in the treaty.

It is, however, stated in a letter of the Secretary of the Interior dated April 6, 1878, contained in the report of the Senate committee to whom the bill under consideration was referred, that in the year 1842 some of these Indians settled upon the lands described in the treaty; and it is further alleged in said report that in 1846 about two hundred more of them were removed to said lands.

The letter of the Secretary of the Interior above referred to contains the following statement concerning these Indian occupants:

From death and the hostility of the settlers, who were drawn in that direction by the fertility of the soil and other advantages, all of the Indians gradually relinquished their selections, until of the Indians who had removed thither from the State of New York only thirty-two remained in 1860.

And the following further statement is made:

The files of the Indian Office show abundant proof that they did not voluntarily. relinquish their occupation.

The proof thus referred to is indeed abundant, and is found in official reports and affidavits made as late as the year 1859. By these it appears that during that year, in repeated instances, Indian men and widows of deceased Indians were driven from their homes by the threats of armed men; that in one case at least the habitation of an Indian woman was burned, and that the kind of outrages were resorted to which too often follow the cupidity of whites and the possession of fertile lands by defenseless and unprotected Indians.

An agent, in an official letter dated August 9, 1859, after detailing the cruel treatment of these occupants of the lands which the Government had given them, writes:

Since these Indians have been placed under my charge, which was, I think, in 1855, I have endeavored to protect them; but complaint after complaint has reached me, and I have reported their situation again and again; and I hope that it will not be long when the Indians who are entitled to land under the decision of the Indian Office shall have it set apart to them.

The same agent, under date of January 18, 1860, referring to these Indians, declares:

These Indians have been driven off their land and claims upon the New York tract by the whites, and they are now very much scattered and many of them are very destitute.

It was found in 1860 that of all the Indians who had prior to that date selected and occupied part of these lands but thirty-two remained, and it seems to have been deemed but justice to them to confirm their selections by some kind of governmental grant or declaration, though it does not appear that any of them had been able to maintain actual possession of all their selected lands against white intrusion. Thus certain special commissioners appointed to examine this subject, under date of May 29, 1860, make the following statement:

In this connection it may be proper to remark that many of the tracts so selected were claimed by lawless men who had compelled the Indians to abandon them under threats of violence; but we are confident that no serious injury will be done to anyone, as the improvements are of but little value.

On the 14th day of September, 1860, certificates were issued to the thirty-two Indians who had made selections of lands and who still survived, with a view of securing to them such selections and at the same time granting to them the number of acres which it was provided they should, have by the treaty of 1838. These certificates were made by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and declared that in conformity with the provisions of the treaty of 1838 there had been assigned and allotted to the person named therein 320 acres of the land designated in said treaty, which land was particularly described in said certificates, which concluded as follows:

And the selection of said tract for the exclusive use and benefit of said reserve, having been approved by the Secretary of the Interior, is not subject to be alienated in fee, leased, or otherwise disposed of except to the United States.

In a letter dated September 13, 1860, from the Indian Commissioner to the agent in the neighborhood of these lands reference is made to the conduct of white intruders upon the same, and the following instructions were given to said agent:

In view of these representations and the fact that these white persons who are in possession of the land are intruders, I have to direct that you will visit the New York Reserve in Kansas at your earliest convenience, accompanied by those Indians living among the Osages to whom said lands have been allotted, with a view to place them in possession of the lands to which they are entitled; and if you should meet with any forcible resistance from white settlers you will report their names to this office, in order that appropriate action may be taken in the premises, and you will inform them that if they do not immediately abandon said lands they will be removed by force. When you shall have given the thirty-two Indians peaceable possession of their lands, or attempted to do so and have been prevented by forcible resistance, you will make a report of your action to this Bureau.

The records of the Indian Bureau do not disclose that any report was ever made by the agent to whom these instructions were given.

In 1861 and 1862 mention was made by the agents of the destitute condition of these Indians and of their being deprived of their lands, and in these years petitions were presented in their behalf asking that justice be done them on account of the failure of the Government to provide them with homes.

In the meantime, and in December, 1860, the remainder of the reserve not allotted to the thirty-two survivors was thrown open to settlement by Executive proclamation. Of course this was followed by increased conflict between the settlers and the Indians. It is presumed that it became dangerous for those to whom lands had been allotted to attempt to gain possession of them. On the 4th day of December, 1865, Agent Snow returned twenty-seven of the certificates of allotment which had not been delivered, and wrote as follows to the Indian Bureau:

A few of these Indians were at one time put in possession of their lands. They were driven off by the whites; one Indian was killed, others wounded, and their houses burned. White men at this time have possession of these lands, and have valuable improvements on them. The Indians are deterred even asking for possession. I would earnestly ask, as agent for these wronged and destitute people, that some measure be adopted by the Government to give these Indians their rights.

An official report made to the Secretary of the Interior dated February 16, 1871, gives the history of these lands, and concludes as follows:

These lands are now all or nearly all occupied by white persons who have driven the Indians from their homes--in some instances with violence. There is great necessity that some relief should be afforded to them by legislation of Congress, authorizing the issue of patents to the allottees or giving them power to sell and convey.

In this way they will be enabled to realize something from the land, and the occupants can secure titles for their homes.

Apparently in the line of this recommendation, and in an attempt to remedy the condition of affairs then existing, an act was passed on the 19th day of February, 1873, permitting heads of families and single persons over 21 years of age who had made settlements and improvements upon and were bona fide claimants and occupants of the lands for which the thirty-two certificates of allotments were issued to enter and purchase at the proper land office such lands so occupied by them, not exceeding 160 acres, upon paying therefor the appraised value of said tracts respectively, to be ascertained by three disinterested and competent appraisers, to be appointed by the Secretary of the Interior, who should report the value of such lands, exclusive of improvements, but that no sale should be made under said act for less than $3.75 per acre.

It was further provided that the entries allowed should be made within twelve months after the promulgation by the Secretary of the Interior of regulations to carry said act into effect, and that the money arising upon such sales should be paid into the Treasury of the United States in trust for and to be paid to the Indians respectively to whom such certificates of allotment had been issued, or to their heirs, upon satisfactory proof of their identity, at any time within five years from the passage of the act, and that in default of such proof the money should become a part of the public moneys of the United States.

It was also further provided that any Indian to whom any certificate of allotment had been issued, and who was then occupying the land allotted thereby, should be entitled to receive a patent therefor.

Pursuant to this statute these lands were appraised. The lowest value per acre fixed by the appraisers was $3.75, and the highest was $10, making the average for the whole $4.90 per acre.

It is reported that only eight pieces, containing 879.76 acres of land taken from six of these Indian allotments, were sold under this statute to the settlers thereon, producing the sum of $4,058.06, and that the price paid in no case was less than $4.50 per acre.

It is proposed by the bill under consideration to sell the remainder of this allotted land to those who failed to avail themselves of the law of 1873 for the sum of $2.50 per acre.

Whatever may be said of the effect of the action of the Indian Bureau in issuing certificates of allotment to individual Indians as it relates to the title of the lands described therein, it was the only way that the Government could perform its treaty obligation to furnish homes for any number of Indians less than a tribe or band; and if these allotments did not vest a title in these individual Indians they secured to them such rights to the lands as the Government was bound to protect and which it could not refuse to confirm if it became necessary by the issuance of patents therefor.

These rights are fully recognized by the statute of 1873, as well as by the bill under consideration.

The right and power of the Government to divest these allottees of their interests under their certificates is so questionable that perhaps it could only be done under the plan proposed, through an estoppel arising from the acceptance of the price for which their allotted lands were sold.

But whatever the effect of a compliance with the provisions of this bill would be upon the title of the settlers to these lands, I can see no fairness or justice in permitting them to enter and purchase such lands at a sum much less than their appraised value in 1873 and for hardly one-half the price paid by their neighbors under the law passed in that year.

The occupancy upon these lands of the settlers seeking relief, and of their grantors, is based upon wrong, violence, and oppression. A continuation of the wrongful exclusion of these Indians from their lands should not inure to the benefit of the wrongdoers. The opportunities afforded by the law of 1873 were neglected, perhaps, in the hope and belief that death would remove the Indians who by their appeals for justice annoyed those who had driven them from their homes, and perhaps in the expectation that the heedlessness of the Government concerning its obligations to the Indians would supply easier terms. The idea is too prevalent that, as against those who by emigration and settlement upon our frontier extend our civilization and prosperity, the rights of the Indians are of but little consequence. But it must be absolutely true that no development is genuine or valuable based upon the violence and cruelty of individuals or the faithlessness of a government.

While it might not result in exact justice or precisely rectify the wrong committed, it may well be that in existing circumstances the interests of the allottees or their heirs demand an adjustment of the kind now proposed. But their lands certainly are worth much more than they were in 1873, and the settlers, if they are not subjected to a reappraisement, should at least pay the price at which the lands were appraised in that year.

If the holders of the interests of the allottees have such a title as will give them a standing in the courts of Kansas, I do not think they need fear defeat by being charged with improvements under the occupying claimants' act, for it has been decided in a case to be found in the twentieth volume of Kansas Reports, at page 374, that--

Neither the title nor possession of the Indian owner, secured by treaty with the United States Government, can be disturbed by State legislation; and the occupying claimants' act has no application in this case.

And yet the delay, uncertainty, and expense of legal contests should be considered.

I suggest that any bill which is passed to adjust the rights of these Indians by such a general plan as is embodied in the bill herewith returned should provide for the payment by the settlers within a reasonable time of an appraised value, and that in case the same is not paid by the respective occupants that the lands be sold at public auction for a price not less than the appraisement.

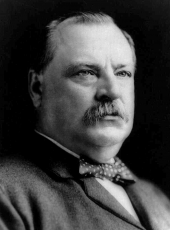

GROVER CLEVELAND

Grover Cleveland, Veto Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/204881