To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:

I transmit herewith, for the consideration of Congress with a view to appropriate legislation in the premises, a report of the Secretary of State, with certain correspondence touching the treaty right of Chinese subjects other than laborers "to go and come of their own free will and accord."

In my annual message of the 8th of December last I said:

In the application of the acts lately passed to execute the treaty of 1880, restrictive of the immigration of Chinese laborers into the United States, individual cases of hardship have occurred beyond the power of the Executive to remedy, and calling for judicial determination.

These cases of individual hardship are due to the ambiguous and derective provisions of the acts of Congress approved respectively on the 6th May, 1882, and 5th July, 1884. The hardship has in some cases been remedied by the action of the courts. In other cases, however, where the phraseology of the statutes has appeared to be conclusive against any discretion on the part of the officers charged with the execution of the law, Chinese persons expressly entitled to free admission under the treaty have been refused a landing and sent back to the country whence they came without being afforded any opportunity to show in the courts or otherwise their right to the privilege of free ingress and egress which it was the purpose of the treaty to secure.

In the language of one of the judicial determinations of the Supreme Court of the United States to which I have referred--

The supposition should not be indulged that Congress, while professing to faithfully execute the treaty stipulations and recognizing the fact that they secure to a certain class the right to go from and come to the United States, intended to make its protection depend upon the performance of conditions which it was physically impossible to perform. (112 U. S. Reports, p. 554, Chew Heong vs. United States. )

The act of July 5, 1884, imposes such an impossible condition in not providing for the admission, under proper certificate, of Chinese travelers of the exempted classes in the cases most likely to arise in ordinary commercial intercourse.

The treaty provisions governing the case are as follows:

ART. I. * * * The limitation or suspension shall be reasonable, and shall apply only to Chinese who may go to the United States as laborers, other classes not being included in the limitations. * * *

ART. II. Chinese subjects, whether proceeding to the United States as teachers, students, merchants, or from curiosity, together with their body and household servants, * * * shall be allowed to go and come of their own free will and accord, and shall be accorded all the rights, privileges, immunities, and exemptions which are accorded to the citizens and subjects of the most favored nation.

Section 6 of the amended Chinese immigration act of 1884 purports to secure this treaty right to the exempted classes named by means of prescribed certificates of their status, which certificates shall be the prima facie and the sole permissible evidence to establish a right of entry into the United States. But it provides in terms for the issuance of certificates in two cases only:

(a) Chinese subjects departing from a port of China; and

(b) Chinese persons ( i.e ., of the Chinese race) who may at the time be subjects of some foreign government other than China, and who may depart for the United States from the ports of such other foreign government.

A statute is certainly most unusual which, purporting to execute the provisions of a treaty with China in respect of Chinese subjects, enacts strict formalities as regards the subjects of other governments than that of China.

It is sufficient that I should call the earnest attention of Congress to the circumstance that the statute makes no provision whatever for the somewhat numerous class of Chinese persons who, retaining their Chinese subjection in some countries other than China, desire to come from such countries to the United States.

Chinese merchants have trading operations of magnitude throughout the world. They do not become citizens or subjects of the country where they may temporarily reside and trade; they continue to be subjects of China, and to them the explicit exemption of the treaty applies. Yet if such a Chinese subject, the head of a mercantile house at Hong Kong or Yokohama or Honolulu or Havana or Colon, desires to come from any of these places to the United States, he is met with the requirement that he must produce a certificate, in prescribed form and in the English tongue, issued by the Chinese Government. If there be at the foreign place of his residence no representative of the Chinese Government competent to issue a certificate in the prescribed form, he can obtain none, and is under the provisions of the present law unjustly debarred from entry into the United States. His usual Chinese passport will not suffice, for it is not in the form which the act prescribes shall be the sole permissible evidence of his right to land. And he can obtain no such certificate from the Government of his place of residence, because he is not a subject or citizen thereof "at the time," or at any time.

There being, therefore, no statutory provision prescribing the terms upon which Chinese persons resident in foreign countries but not subjects or citizens of such countries may prove their status and rights as members of the exempted classes in the absence of a Chinese representative in such country, the Secretary of the Treasury, in whom the execution of the act of July 5, 1884, was vested, undertook to remedy the omission by directing the revenue officers to recognize as lawful certificates those issued in favor of Chinese subjects by the Chinese consular and diplomatic officers at the foreign port of departure, when viseed by the United States representative thereat. This appears to be a just application of the spirit of the law, although enlarging its letter, and in adopting this rule he was controlled by the authority of high judicial decision as to what evidence is necessary to establish the fact that an individual Chinaman belongs to the exempted class.

He, however, went beyond the spirit of the act and the judicial decisions, by providing, in a circular dated January 14, 1885, for the original issuance of such a certificate by the United States consular officer at the port of departure, in the absence of a Chinese diplomatic or consular representative thereat; for it is clear that the act of Congress contemplated the intervention of the United States consul only in a supervisory capacity, his function being to check the proceeding and see that no abuse of the privilege followed. The power or duty of original certification is wholly distinct from that supervisory function. It either dispenses with the foreign certificate altogether, leaving the consular vise to stand alone and sufficient, or else it combines in one official act the distinct functions of certification and verification of the fact certified.

The official character attaching to the consular certification contemplated by the unamended circular of January 14, 1885, is to be borne in mind. It is not merely prima facie evidence of the status of the bearer, such as the courts may admit in their discretion; it was prescribed as an official attestation, on the strength of which the customs officers at the port of entry were to admit the bearer without further adjudication of his status unless question should arise as to the truth of the certificate itself.

It became, therefore, necessary to amend the circular of January 14, 1885, and this was done on the 13th of June following, by striking out the clause prescribing original certification of status by the United States consuls. The effect of this amendment is to deprive any certificate the United States consuls may issue of the value it purported to possess as sole permissible evidence under the statute when its issuance was prescribed by Treasury regulations. There is, however, nothing to prevent consuls giving certificates of facts within their knowledge to be received as evidence in the absence of statutory authentication.

The complaint of the Chinese minister in his note of March 24, 1886, is that the Chinese merchant Lay Sang, of the house of King Lee & Co., of San Francisco, having arrived at San Francisco from Hongkong and exhibited a certificate of the United States consul at Hongkong as to his status as a merchant, and consequently exempt under the treaty, was refused permission to land and was sent back to Hongkong by the steamer which brought him. While the certificate he bore was doubtless insufficient under the present law, it is to be remembered that there is at Hongkong no representative of the Government of China competent or authorized to issue the certificate required by the statute. The intent of Congress to legislate in execution of the treaty is thus defeated by a prohibition directly contrary to the treaty, and conditions are exacted which, in the words of the Supreme Court hereinbefore quoted, "it was physically impossible to perform."

This anomalous feature of the act should be reformed as speedily as possible, in order that the occurrence of such cases may be avoided and the imputation removed which would otherwise rest upon the good faith of the United States in the execution of their solemn treaty engagements.

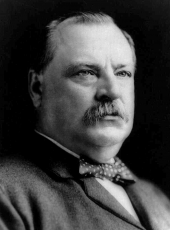

GROVER CLEVELAND

Grover Cleveland, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/205079