To the Senate and House of Representatives.

I find it necessary to recommend to Congress a revision of the laws relating to the direct and contingent expenses of our intercourse with foreign nations, and particularly of the act of May 1, 1810, entitled "An act fixing the compensation of public ministers and of consuls residing on the coast of Barbary, and for other purposes."

A letter from the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury to the Secretary of State, herewith transmitted, which notices the difficulties incident to the settlement of the accounts of certain diplomatic agents of the United States, serves to show the necessity of this revision. This branch of the Government is incessantly called upon to sanction allowances which not unfrequently appear to have just and equitable foundations in usage, but which are believed to be incompatible with the provisions of the act of 1810. The letter from the Fifth Auditor contains a description of several claims of this character which are submitted to Congress as the only tribunal competent to afford the relief to which the parties consider themselves entitled.

Among the most prominent questions of this description are the following:

1 . Claims for outfits by ministers and charges d' affaires duly appointed by the President and Senate.

The act of 1790, regulating the expenditures for foreign intercourse, provided "that, exclusive of an outfit, which shall in no case exceed one year's full salary to the minister plenipotentiary or charge d'affaires to whom the same may be allowed, the President shall not allow to any minister plenipotentiary a greater sum than at the rate of $9,000 per annum as a compensation for all his personal services and other expenses, nor a greater sum for the same than $4,500 per annum to a charge d'affaires." By this provision the maximum of allowance only was fixed, leaving the question as to any outfit, either in whole or in part, to the discretion of the President, to be decided according to circumstances. Under it a variety of cases occurred, in which outfits having been given to diplomatic agents on their first appointment, afterwards, upon their being transferred to other courts or sent upon special and distinct missions, full or half outfits were again allowed.

This act, it will be perceived, although it fixes the maximum of outfit, is altogether silent as to the circumstances under which outfits might be allowed; indeed, the authority to allow them at all is not expressly conveyed, but only incidentally adverted to in limiting the amount. This limitation continued to be the only restriction upon the Executive until 1810, the act of 1790 having been kept in force till that period by five successive reenactments, in which it is either referred to by means of its title or its terms are repeated verbatim. In 1810 an act passed wherein the phraseology which had been in use for twenty years is departed from. Fixing the same limits precisely to the amount of salaries and outfits to ministers and charges as had been six times fixed since 1790, it differs from preceding acts by formally conveying an authority to allow an outfit to "a minister plenipotentiary or charge d'affaires on going from the United States to any foreign country; " and, in addition to this specification of the circumstances under which the outfit may be allowed, it contains one of the conditions which shall be requisite to entitle a charge or secretary to the compensation therein provided.

Upon a view of all the circumstances connected with the subject I can not permit myself to doubt that it was with reference to the practice of multiplying outfits to the same person and in the intention of prohibiting it in future that this act was passed.

It being, however, frequently deemed advantageous to transfer ministers already abroad from one court to another, or to employ those who were resident at a particular court upon special occasions elsewhere, it seems to have been considered that it was not the intention of Congress to restrain the Executive from so doing. It was further contended that the President being left free to select for ministers citizens, whether at home or abroad, a right on the part of such ministers to the usual emoluments followed as a matter of course. This view was sustained by the opinion of the law officer of the Government, and the act of 1810 was construed to leave the whole subject of salary and outfit where it found it under the law of 1790; that is to say, completely at the discretion of the President, without any other restriction than the maximum already fixed by that law. This discretion has from time to time been exercised by successive Presidents; but whilst I can not but consider the restriction in this respect imposed by the act of 1810 as inexpedient, I can not feel myself justified in adopting a construction which defeats the only operation of which this part of it seems susceptible; at least, not unless Congress, after having the subject distinctly brought to their consideration, should virtually give their assent to that construction. Whatever may be thought of the propriety of giving an outfit to secretaries of legation or others who may be considered as only temporarily charged with the affairs intrusted to them, I am impressed with the justice of such an allowance in the case of a citizen who happens to be abroad when first appointed, and that of a minister already in place, when the public interest requires his transfer, and, from the breaking up of his establishment and other circumstances connected with the change, he incurs expenses to which he would not otherwise have been subjected.

II. Claims for outfits and salaries by charges d 'affaires and secretaries of legation who have not been appointed by the President by and with the advice and consent of the Senate .

By the second section of the act of 1810 it is provided--

That to entitle any charge d'affaires or secretary of any legation or embassy to any foreign country, or secretary of any minister plenipotentiary, to the compensation hereinbefore provided they shall respectively be appointed by the President of the United States, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate; but in the recess of the Senate the President is hereby authorized to make such appointments, which shall be submitted to the Senate at the next session thereafter for their advice and consent; and no compensation shall be allowed to any charge d'affaires or any of the secretaries hereinbefore described who shall not be appointed as aforesaid.

Notwithstanding the explicit language of this act, claims for outfits and salaries have been made--and allowed at the Treasury--by charges d'affaires and secretaries of legation who had not been appointed in the manner specified. Among the accompanying documents will be found several claims of this description, of which a detailed statement is given in the letter of the Fifth Auditor. The case of Mr. William B. Lawrence, late charge d'affaires at London, is of a still more peculiar character, in consequence of his having actually drawn his outfit and salary from the bankers employed by the Government, and from the length of time he officiated in that capacity. Mr. Lawrence's accounts were rendered to the late Administration, but not settled. I have refused to sanction the allowance claimed, because the law does not authorize it, but have refrained from directing any proceedings to compel a reimbursement of the money thus, in my judgment, illegally received until an opportunity should be afforded to Congress to pass upon the equity of the claim.

Appropriations are annually and necessarily made "for the contingent expenses of all the missions abroad" and "for the contingent expenses of foreign intercourse," and the expenditure of these funds intrusted to the discretion of the President. It is out of those appropriations that allowances of this character have been claimed, and, it is presumed, made. Deeming, however, that the discretion thus committed to the Executive does not extend to the allowance of charges prohibited by express law, I have felt it my duty to refer all existing claims to the action of Congress, and to submit to their consideration whether any alteration of the law in this respect is necessary.

III. The allowance of a quarter' s salary to ministers and charges d' affaires to defray their expenses home.

This allowance has been uniformly made, but is without authority by law. Resting in Executive discretion, it has, according to circumstances, been extended to cases where the ministers died abroad, to defray the return of his family, and was recently claimed in a case where the minister had no family, on grounds of general equity. A charge of this description can hardly be regarded as a contingent one, and if allowed at all must be in lieu of salary. As such it is altogether arbitrary, although it is not believed that the interests of the Treasury are, upon the whole, much affected by the substitution. In some cases the allowance is for a longer period than is occupied in the return of the minister; in others, for one somewhat less; and it seems to do away all inducement to unnecessary delay. The subject is, however, susceptible of positive regulation by law, and it is, on many accounts, highly expedient that it should be placed on that footing. I have therefore, without directing any alteration in the existing practice, felt it my duty to bring it to your notice.

IV. Traveling and other expenses in following the court in cases where its residence is not stationary.

The only legations by which expenses of this description are incurred and charged are those to Spain and the Netherlands, and to them they have on several occasions been allowed. Among the documents herewith communicated will be found, with other charges requiring legislative interference, an account for traveling expenses, with a statement of the grounds upon which their reimbursement is claimed. This account has been suspended by the officer of the Treasury to whom its settlement belongs; and as the question will be one of frequent recurrence, I have deemed the occasion a fit one to submit the whole subject to the revision of Congress. The justice of these charges for extraordinary expenses unavoidably incurred has been admitted by former Administrations and the claims allowed. My difficulty grows out of the language of the act of 1810, which expressly declares that the salary and outfit it authorizes to the minister and charge d'affaires shall be "a compensation for all his personal services and expenses." The items which ordinarily form the contingent expenses of a foreign mission are of a character distinct from the personal expenses of the minister. The difficulty of regarding those now referred to in that light is obvious. There are certainly strong considerations of equity in favor of a remuneration for them at the two Courts where they are alone incurred, and if such should be the opinion of Congress it is desirable that authority to make it should be expressly conferred by law rather than continue to rest upon doubtful construction.

V. Charges of consuls for discharging diplomatic functions, without appointment, during a temporary vacancy in the office of charge d' affaires.

It has sometimes happened that consuls of the United States, upon the occurrence of vacancies at their places of residence in the diplomatic offices of the United States by the death or retirement of our minister or charge d'affaires, have taken under their care the papers of such missions and usefully discharged diplomatic functions in behalf of their Government and fellow-citizens till the vacancies were regularly filled. In some instances this is stated to have been done to the abandonment of other pursuits and at a considerably increased expense of living. There are existing claims of this description, which can not be finally adjusted or allowed without the sanction of Congress. A particular statement of them accompanies this communication.

The nature of this branch of the public service makes it necessary to commit portions of the expenses incurred in it to Executive discretion; but it is desirable that such portions should be as small as possible. The purity and permanent success of our political institutions depend in a great measure upon definite appropriations and a rigid adherence to the enactments of the Legislature disposing of public money. My desire is to have the subject placed upon a more simple and precise, but not less liberal, footing than it stands on at present, so far as that may be found practicable. An opinion that the salaries allowed by law to our agents abroad are in many cases inadequate is very general, and it is reasonable to suppose that this impression has not been without its influence in the construction of the laws by which those salaries are fixed. There are certainly motives which it is difficult to resist to an increased expense on the part of some of our functionaries abroad greatly beyond that which would be required at home.

Should Congress be of opinion that any alteration for the better can be made, either in the rate of salaries now allowed or in the rank and gradation of our diplomatic agents, or both, the present would be a fit occasion for a revision of the whole subject.

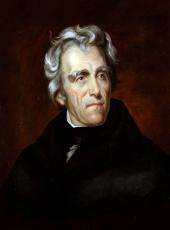

ANDREW JACKSON

Andrew Jackson, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/201099