To the House of Representatives:

On the 9th day of December, 1876, the following resolution of the House of Representatives was received, namely:

Resolved , That the President be requested, if not incompatible with the public interest, to transmit to this House copies of any and all orders or directions emanating from him or from either of the Executive Departments of the Government to any military commander or civil officer with reference to the service of the Army, or any portion thereof, in the States of Virginia, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida since the 1st of August last, together with reports by telegraph or otherwise from either or any of said military commanders or civil officers.

It was immediately or soon thereafter referred to the Secretary of 'War and the Attorney-General, the custodians of all retained copies of "orders or directions" given by the Executive Departments of the Government covered by the above inquiry, together with all information upon which such "orders or directions" were given.

The information, it will be observed, is voluminous, and, with the limited clerical force in the Department of Justice, has consumed the time up to the present. Many of the communications accompanying this have been already made public in connection with messages heretofore sent to Congress. This class of information includes the important documents received from the governor of South Carolina and sent to Congress with my message on the subject of the Hamburg massacre; also the documents accompanying my response to the resolution of the House of Representatives in regard to the soldiers stationed at Petersburg.

There have also come to me and to the Department of Justice, from time to time, other earnest written communications from persons holding public trusts and from others residing in the South, some of which I append hereto as bearing upon the precarious condition of the public peace in those States. These communications I have reason to regard as made by respectable and responsible men. Many of them deprecate the publication of their names as involving danger to them personally.

The reports heretofore made by committees of Congress of the results of their inquiries in Mississippi and Louisiana, and the newspapers of several States recommending" the Mississippi plan," have also furnished important data for estimating the danger to the public peace and order in those States.

It is enough to say that these different kinds and sources of evidence have left no doubt whatever in my mind that intimidation has been used, and actual violence, to an extent requiring the aid of the United States Government, where it was practicable to furnish such aid, in South Carolina, in Florida, and in Louisiana, as well as in Mississippi, in Alabama, and in Georgia.

The troops of the United States have been but sparingly used, and in no case so as to interfere with the free exercise of the right of suffrage. Very few troops were available for the purpose of preventing or suppressing the violence and intimidation existing in the States above named. In no case, except that of South Carolina, was the number of soldiers in any State increased in anticipation of the election, saving that twenty-four men and an officer were sent from Fort Foote to Petersburg, Va., where disturbances were threatened prior to the election.

No troops were stationed at the voting places. In Florida and in Louisiana, respectively, the small number of soldiers already in the said States were stationed at such points in each State as were most threatened with violence, where they might be available as a posse for the officer whose duty it was to preserve the peace and prevent intimidation of voters. Such a disposition of the troops seemed to me reasonable and justified by law and precedent, while its omission would have been inconsistent with the constitutional duty of the President of the United States "to take care that the laws be faithfully executed." The statute expressly forbids the bringing of troops to the polls "except where it is necessary to keep the peace," implying that to keep the peace it may be done. But this even, so far as I am advised, has not in any case been done. The stationing of a company or part of a company in the vicinity, where they would be available to prevent riot, has been the only use made of troops prior to and at the time of the elections. Where so stationed, they could be called in an emergency requiring it by a marshal or deputy marshal as a posse to aid in suppressing unlawful violence. The evidence which has come to me has left me no ground to doubt that if there had been more military force available it would have been my duty to have disposed of it in several States with a view to the prevention of the violence and intimidation which have undoubtedly contributed to the defeat of the election law in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, as well as in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida.

By Article IV, section 4, of the Constitution--

The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a republican form of government, and shall protect each of them against invasion, and on application of the legislature, or of the executive (when the legislature can not be convened), against domestic violence.

By act of Congress (U. S. Revised Statutes, secs. 1034, 1035) the President, in case of "insurrection in any State" or of "unlawful obstruction to the enforcement of the laws of the United States by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings," or whenever "domestic violence in any State so obstructs the execution of the laws thereof and of the United States as to deprive any portion of the people of such State" of their civil or political rights, is authorized to employ such parts of the land and naval forces as he may deem necessary to enforce the execution of the laws and preserve the peace and sustain the authority of the State and of the United States. Acting under this title (69) of the Revised Statutes United States, I accompanied the sending of troops to South Carolina with a proclamation such as is therein prescribed.

The President is also authorized by act of Congress "to employ such part of the land or naval forces of the United States * * * as shall be necessary to prevent the violation and to enforce the due execution of the provisions" of title 24 of the Revised Statutes of the United States, for the protection of the civil rights of citizens, among which is the provision against conspiracies "to prevent, by force, intimidation, or threat, any citizen who is lawfully entitled to vote from giving his support or advocacy in a legal manner toward or in favor of the election of any lawfully qualified person as an elector for President or Vice-President or as a member of Congress of the United States." (U. S. Revised Statutes, sec. 1989. )

In cases falling under this title I have not considered it necessary to issue a proclamation to precede or accompany the employment of such part of the Army as seemed to be necessary.

In case of insurrection against a State government or against the Government of the United States a proclamation is appropriate; but in keeping the peace of the United States at an election at which Members of Congress are elected no such call from the State or proclamation by the President is prescribed by statute or required by precedent.

In the case of South Carolina insurrection and domestic violence against the State government were clearly shown, and the application of the governor rounded thereon was duly presented, and I could not deny his constitutional request without abandoning my duty as the Executive of the National Government.

The companies stationed in the other States have been employed to secure the better execution of the laws of the United States and to preserve the peace of the United States.

After the election had been had, and where violence was apprehended by which the returns from the counties and precincts might be destroyed, troops were ordered to the State of Florida, and those already in Louisiana were ordered to the points in greatest danger of violence.

I have not employed troops on slight occasions, nor in any case where it has not been necessary to the enforcement of the laws of the United States. In this I have been guided by the Constitution and the laws which have been enacted and the precedents which have been formed under it.

It has been necessary to employ troops occasionally to overcome resistance to the internal-revenue laws from the time of the resistance to the collection of the whisky tax in Pennsylvania, under Washington, to the present time.

In 1854, when it was apprehended that resistance would be made in Boston to the seizure and return to his master of a fugitive slave, the troops there stationed were employed to enforce the master's right under the Constitution, and troops stationed at New York were ordered to be in readiness to go to Boston if it should prove to be necessary.

In 1859, when John Brown, with a small number of men, made his attack upon Harpers Ferry, the President ordered United States troops to assist in the apprehension and suppression of him and his party without a formal call of the legislature or governor of Virginia and without proclamation of the President.

Without citing further instances in which the Executive has exercised his power, as Commander of the Army and Navy, to prevent or suppress resistance to the laws of the United States, or where he has exercised like authority in obedience to a call from a State to suppress insurrection, I desire to assure both Congress and the country that it has been my purpose to administer the executive powers of the Government fairly, and in no instance to disregard or transcend the limits of the Constitution.

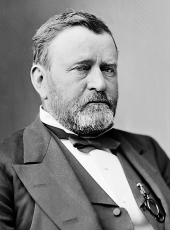

U. S. GRANT.

Ulysses S. Grant, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/203661