To the House of Representatives of the United States:

In compliance with the resolution of the House of the 5th ultimo, requesting me to cause to be laid before the House so much of the correspondence between the Government of the United States and the new States of America, or their ministers, respecting the proposed congress or meeting of diplomatic agents at Panama, and such information respecting the general character of that expected congress as may be in my possession and as may, in my opinion, be communicated without prejudice to the public interest, and also to inform the House, so far as in my opinion the public interest may allow, in regard to what objects the agents of the United States are expected to take part in the deliberations of that congress, I now transmit to the House a report from the Secretary of State, with the correspondence and information requested by the resolution.

With regard to the objects in which the agents of the United States are expected to take part in the deliberations of that congress, I deem it proper to premise that these objects did not form the only, nor even the principal, motive for my acceptance of the invitation. My first and greatest inducement was to meet in the spirit of kindness and friendship an overture made in that spirit by three sister Republics of this hemisphere.

The great revolution in human affairs which has brought into existence, nearly at the same time, eight sovereign and independent nations in our own quarter of the globe has placed the United States in a situation not less novel and scarcely less interesting than that in which they had found themselves by their own transition from a cluster of colonies to a nation of sovereign States. The deliverance of the Southern American Republics from the oppression under which they had been so long afflicted was hailed with great unanimity by the people of this Union as among the most auspicious events of the age. On the 4th of May, 1822, an act of Congress made an appropriation of $100,000 "for such missions to the independent nations on the American continent as the President of the United States might deem proper." In exercising the authority recognized by this act my predecessor, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate appointed successively ministers plenipotentiary to the Republics of Colombia, Buenos Ayres, Chili, and Mexico. Unwilling to raise among the fraternity of freedom questions of precedency and etiquette, which even the European monarchs had of late found it necessary in a great measure to discard, he dispatched these ministers to Colombia, Buenos Ayres, and Chili without exacting from those Republics, as by the ancient principles of political primogeniture he might have done, that the compliment of a plenipotentiary mission should have been paid first by them to the United States. The instructions, prepared under his direction, to Mr. Anderson, the first of our ministers to the southern continent, contain at much length the general principles upon which he thought it desirable that our relations, political and commercial, with these our new neighbors should be established for their benefit and ours and that of the future ages of our posterity. A copy of so much of these instructions as relates to these general subjects is among the papers now transmitted to the House. Similar instructions were furnished to the ministers appointed to Buenos Ayres, Chili, and Mexico, and the system of social intercourse which it was the purpose of those missions to establish from the first opening of our diplomatic relations with those rising nations is the most effective exposition of the principles upon which the invitation to the congress at Panama has been accepted by me, as well as of the objects of negotiation at that meeting, in which it was expected that our plenipotentiaries should take part.

The House will perceive that even at the date of these instructions the first treaties between some of the southern Republics had been concluded, by which they had stipulated among themselves this diplomatic assembly at Panama. And it will be seen with what caution, so far as it might concern the policy of the United States, and at the same time with what frankness and good will toward those nations, he gave countenance to their design of inviting the United States to this high assembly for consultation upon American interests. It was not considered a conclusive reason for declining this invitation that the proposal for assembling such a Congress had not first been made by ourselves. It had sprung from the urgent, immediate, and momentous common interests of the great communities struggling for independence, and, as it were, quickening into life. From them the proposition to us appeared respectful and friendly; from us to them it could scarcely have been made without exposing ourselves to suspicions of purposes of ambition, if not of domination, more suited to rouse resistance and excite distrust than to conciliate favor and friendship. The first and paramount principle upon which it was deemed wise and just to lay the corner stone of all our future relations with them was disinterestedness; the next was cordial good will to them; the third was a claim of fair and equal reciprocity. Under these impressions when the invitation was formally and earnestly given, had it even been doubtful whether any of the objects proposed for consideration and discussion at the Congress were such as that immediate and important interests of the United States would be affected by the issue, I should, nevertheless, have determined so far as it depended upon me to have accepted the invitation and to have appointed ministers to attend the meeting. The proposal itself implied that the Republics by whom it was made believed that important interests of ours or of theirs rendered our attendance there desirable. They had given us notice that in the novelty of their situation and in the spirit of deference to our experience they would be pleased to have the benefit of our friendly counsel. To meet the temper with which this proposal was made with a cold repulse was not thought congenial to that warm interest in their welfare with which the people and Government of the Union had hitherto gone hand in hand through the whole progress of their revolution. To insult them by a refusal of their overture, and then invite them to a similar assembly to be called by ourselves, was an expedient which never presented itself to the mind. I would have sent ministers to the meeting had it been merely to give them such advice as they might have desired, even with reference to their own interests, not involving ours. I would have sent them had it been merely to explain and set forth to them our reasons for declining any proposal of specific measures to which they might desire our concurrence, but which we might deem incompatible with our interests or our duties. In the intercourse between nations temper is a missionary perhaps more powerful than talent. Nothing was ever lost by kind treatment. Nothing can be gained by sullen repulses and aspiring pretensions.

But objects of the highest importance, not only to the future welfare of the whole human race, but bearing directly upon the special interests of this Union, will engage the deliberations of the congress of Panama whether we are represented there or not. Others, if we are represented, may be offered by our plenipotentiaries for consideration having in view both these great results--our own interests and the improvement of the condition of man upon earth. It may be that in the lapse of many centuries no other opportunity so favorable will be presented to the Government of the United States to subserve the benevolent purposes of Divine Providence; to dispense the promised blessings of the Redeemer of Mankind; to promote the prevalence in future ages of peace on earth and good will to man, as will now be placed in their power by participating in the deliberations of this congress.

Among the topics enumerated in official papers published by the Republic of Colombia, and adverted to in the correspondence now communicated to the House, as intended to be presented for discussion at Panama, there is scarcely one in which the result of the meeting will not deeply affect the interests of the United States. Even those in which the belligerent States alone will take an active part will have a powerful effect upon the state of our relations with the American, and probably with the principal European, States. Were it merely that we might be correctly and speedily informed of the proceedings of the congress and of the progress and issue of their negotiations, I should hold it advisable that we should have an accredited agency with them, placed in such confidential relations with the other members as would insure the authenticity and the safe and early transmission of its reports. Of the same enumerated topics are the preparation of a manifesto setting forth to the world the justice of their cause and the relations they desire to hold with other Christian powers, and to form a convention of navigation and commerce applicable both to the confederated States and to their allies.

It will be within the recollection of the House that immediately after the close of the war of our independence a measure closely analogous to this congress of Panama was adopted by the Congress of our Confederation, and for purposes of precisely the same character. Three commissioners with plenipotentiary powers were appointed to negotiate treaties of amity, navigation, and commerce with all the principal powers of Europe. They met and resided for that purpose about one year at Paris, and the only result of their negotiations at that time was the first treaty between the United States and Prussia--memorable in the diplomatic annals of the world, and precious as a monument of the principles, in relation to commerce and maritime warfare, with which our country entered upon her career as a member of the great family of independent nations. This treaty, prepared in conformity with the instructions of the American plenipotentiaries, consecrated three fundamental principles of the foreign intercourse which the Congress of that period were desirous of establishing: First, equal reciprocity and the mutual stipulation of the privileges of the most favored nation in the commercial exchanges of peace; secondly, the abolition of private war upon the ocean, and thirdly, restrictions favorable to neutral commerce upon belligerent practices with regard to contraband of war and blockades. A painful, it may be said a calamitous, experience of more than forty years has demonstrated the deep importance of these same principles to the peace and prosperity of this nation and to the welfare of all maritime States, and has illustrated the profound wisdom with which they were assumed as cardinal points of the policy of the Union.

At that time in the infancy of their political existence, under the influence of those principles of liberty and of right so congenial to the cause in which they had just fought and triumphed, they were able but to obtain the sanction of one great and philosophical, though absolute, sovereign in Europe to their liberal and enlightened principles. They could obtain no more. Since then a political hurricane has gone over three-fourths of the civilized portions of the earth, the desolation of which it may with confidence be expected is passing away, leaving at least the American atmosphere purified and refreshed. And now at this propitious moment the new-born nations of this hemisphere, assembling by their representatives at the isthmus between its two continents to settle the principles of their future international intercourse with other nations and with us, ask in this great exigency for our advice upon those very fundamental maxims which we from our cradle at first proclaimed and partially succeeded to introduce into the code of national law.

Without recurring to that total prostration of all neutral and commercial rights which marked the progress of the late European wars, and which finally involved the United States in them, and adverting only to our political relations with these American nations, it is observable that while in all other respects those relations have been uniformly and without exception of the most friendly and mutually satisfactory character, the only causes of difference and dissension between us and them which ever have arisen originated in those never-failing fountains of discord and irritation--discriminations of commercial favor to other, nations, licentious privateers, and paper blockades. I can not without doing injustice to the Republics of Buenos Ayres and Colombia forbear to acknowledge the candid and conciliatory spirit with which they have repeatedly yielded to our friendly representations and remonstrances on these subjects--in repealing discriminative laws which operated to our disadvantage and in revoking the commissions of their privateers, to which Colombia has added the magnanimity of making reparation for unlawful captures by some of her cruisers and of assenting in the midst of war to treaty stipulations favorable to neutral navigation. But the recurrence of these occasions of complaint has rendered the renewal of the discussions which result in the removal of them necessary, while in the meantime injuries are sustained by merchants and other individuals of the United States which can not be repaired, and the remedy lingers in overtaking the pernicious operation of the mischief. The settlement of general principles pervading with equal efficacy all the American States can alone put an end to these evils, and can alone be accomplished at the proposed assembly.

If it be true that the noblest treaty of peace ever mentioned in history is that by which the Carthagenians were bound to abolish the practice of sacrificing their own children because it was stipulated in favor of human nature, I can not exaggerate to myself the unfading glory with which these United States will go forth in the memory of future ages if by their friendly counsel, by their moral influence, by the power of argument and persuasion alone they can prevail upon the American nations at Panama to stipulate by general agreement among themselves, and so far as any of them may be concerned, the perpetual abolition of private war upon the ocean. And if we can not yet flatter ourselves that this may be accomplished, as advances toward it the establishment of the principle that the friendly flag shall cover the cargo, the curtailment of contraband of war, and the proscription of fictitious paper blockades--engagements which we may reasonably hope will not prove impracticable will, if successfully inculcated, redound proportionally to our honor and drain the fountain of many a future sanguinary war.

The late President of the United States, in his message to Congress of the 2d December, 1823, while announcing the negotiation then pending with Russia, relating to the northwest coast of this continent, observed that the occasion of the discussions to which that incident had given rise had been taken for asserting as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States were involved that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they had assumed and maintained, were thenceforward not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European power. The principle had first been assumed in that negotiation with Russia. It rested upon a course of reasoning equally simple and conclusive. With the exception of the existing European colonies, which it was in nowise intended to disturb, the two continents consisted of several sovereign and independent nations, whose territories covered their whole surface. By this their independent condition the United States enjoyed the right of commercial intercourse with every part of their possessions. To attempt the establishment of a colony in those possessions would be to usurp to the exclusion of others a commercial intercourse which was the common possession of all. It could not be done without encroaching upon existing rights of the United States. The Government of Russia has never disputed these positions nor manifested the slightest dissatisfaction at their having been taken. Most of the new American Republics have declared their entire assent to them, and they now propose, among the subjects of consultation at Panama, to take into consideration the means of making effectual the assertion of that principle, as well as the means of resisting interference from abroad with the domestic concerns of the American Governments.

In alluding to these means it would obviously be premature at this time to anticipate that which is offered merely as matter for consultation, or to pronounce upon those measures which have been or may be suggested. The purpose of this Government is to concur in none which would import hostility to Europe or justly excite resentment in any of her States. Should it be deemed advisable to contract any conventional engagement on this topic, our views would extend no further than to a mutual pledge of the parties to the compact to maintain the principle in application to its own territory, and to permit no colonial lodgments or establishment of European jurisdiction upon its own soil; and with respect to the obtrusive interference from abroad--if its future character may be inferred from that which has been and perhaps still is exercised in more than one of the new States--a joint declaration of its character and exposure of it to the world may be probably all that the occasion would require. Whether the United States should or should not be parties to such a declaration may justly form a part of the deliberation. That there is an evil to be remedied needs little insight into the secret history of late years to know, and that this remedy may best be concerted at the Panama meeting deserves at least the experiment of consideration. A concert of measures having reference to the more effectual abolition of the African slave trade and the consideration of the light in which the political condition of the island of Hayti is to be regarded are also among the subjects mentioned by the minister from the Republic of Colombia as believed to be suitable for deliberation at the congress. The failure of the negotiations with that Republic undertaken during the late Administration, for the suppression of that trade, in compliance with a resolution of the House of Representatives, indicates the expediency of listening with respectful attention to propositions which may contribute to the accomplishment of the great end which was the purpose of that resolution, while the result of those negotiations will serve as admonition to abstain from pledging this Government to any arrangement which might be expected to fail of obtaining the advice and consent of the Senate by a constitutional majority to its ratification.

Whether the political condition of the island of Hayti shall be brought at all into discussion at the meeting may be a question for preliminary advisement. There are in the political constitution of Government of that people circumstances which have hitherto forbidden the acknowledgment of them by the Government of the United States as sovereign and independent. Additional reasons for withholding that acknowledgment have recently been seen in their acceptance of a nominal sovereignty by the grant of a foreign prince under conditions equivalent to the concession by them of exclusive commercial advantages to one nation, adapted altogether to the state of colonial vassalage and retaining little of independence but the name. Our plenipotentiaries will be instructed to present these views to the assembly at Panama, and should they not be concurred in to decline acceding to any arrangement which may be proposed upon different principles.

The condition of the islands of Cuba and Porto Rico is of deeper import and more immediate bearing upon the present interests and future prospects of our Union. The correspondence herewith transmitted will show how earnestly it has engaged the attention of this Government. The invasion of both those islands by the united forces of Mexico and Colombia is avowedly among the objects to be matured by the belligerent States at Panama. The convulsions to which, from the peculiar composition of their population, they would be liable in the event of such an invasion, and the danger therefrom resulting of their falling ultimately into the hands of some European power other than Spain, will not admit of our looking at the consequences to which the congress at Panama may lead with indifference. It is unnecessary to enlarge upon this topic or to say more than that all our efforts in reference to this interest will be to preserve the existing state of things, the tranquillity of the islands, and the peace and security of their inhabitants.

And lastly, the congress of Panama is believed to present a fair occasion for urging upon all the new nations of the south the just and liberal principles of religious liberty; not by any interference whatever in their internal concerns, but by claiming for our citizens whose occupations or interests may call them to occasional residence in their territories the inestimable privilege of worshipping their Creator according to the dictates of their own consciences. This privilege, sanctioned by the customary law of nations and secured by treaty stipulations in numerous national compacts, secured even to our own citizens in the treaties with Colombia and with the Federation of Central America, is yet to be obtained in the other South American States and Mexico. Existing prejudices are still struggling against it, which may, perhaps, be more successfully combated at this general meeting than at the separate seats of Government of each Republic.

I can scarcely deem it otherwise than superfluous to observe that the assembly will be in its nature diplomatic and not legislative; that nothing can be transacted there obligatory upon any one of the States to be represented at the meeting, unless with the express concurrence of its own representatives, nor even then, but subject to the ratification of its constitutional authority at home. The faith of the United States to foreign powers can not otherwise be pledged. I shall, indeed, in the first instance, consider the assembly as merely consultative; and although the plenipotentiaries of the United States will be empowered to receive and refer to the consideration of their Government any proposition from the other parties to the meeting, they will be authorized to conclude nothing unless subject to the definitive sanction of this Government in all its constitutional forms. It has therefore seemed to me unnecessary to insist that every object to be discussed at the meeting should be specified with the precision of a judicial sentence or enumerated with the exactness of a mathematical demonstration. The purpose of the meeting itself is to deliberate upon the great and common interests of several new and neighboring nations. If the measure is new and without precedent, so is the situation of the parties to it. That the purposes of the meeting are somewhat indefinite, far from being an objection to it is among the cogent reasons for its adoption. It is not the establishment of principles of intercourse with one, but with seven or eight nations at once. That before they have had the means of exchanging ideas and communicating with one another in common upon these topics they should have definitively settled and arranged them in concert is to require that the effect should precede the cause; it is to exact as a preliminary to the meeting that for the accomplishment of which the meeting itself is designed.

Among the inquiries which were thought entitled to consideration before the determination was taken to accept the invitation was that whether the measure might not have a tendency to change the policy, hitherto invariably pursued by the United States, of avoiding all entangling alliances and all unnecessary foreign connections.

Mindful of the advice given by the father of our country in his Farewell Address, that the great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is, in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible, and faithfully adhering to the spirit of that admonition, I can not overlook the reflection that the counsel of Washington in that instance, like all the counsels of wisdom, was rounded upon the circumstances in which our country and the world around us were situated at the time when it was given; that the reasons assigned by him for his advice were that Europe had a set of primary interests which to us had none or a very remote relation; that hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which were essentially foreign to our concerns; that our detached and distant situation invited and enabled us to pursue a different course; that by our union and rapid growth, with an efficient Government, the period was not far distant when we might defy material injury from external annoyance, when we might take such an attitude as would cause our neutrality to be respected, and, with reference to belligerent nations, might choose peace or war, as our interests, guided by justice, should counsel.

Compare our situation and the circumstances of that time with those of the present day, and what, from the very words of Washington then, would be his counsels to his countrymen now? Europe has still her set of primary interests, with which we have little or a remote relation. Our distant and detached situation with reference to Europe remains the same. But we were then the only independent nation of this hemisphere, and we were surrounded by European colonies, with the greater part of which we had no more intercourse than with the inhabitants of another planet. Those colonies have now been transformed into eight independent nations, extending to our very borders, seven of them Republics like ourselves, with whom we have an immensely growing commercial, and must have and have already important political, connections; with reference to whom our situation is neither distant nor detached; whose political principles and systems of government, congenial with our own, must and will have an action and counteraction upon us and ours to which we can not be indifferent if we would.

The rapidity of our growth, and the consequent increase of our strength, has more than realized the anticipations of this admirable political legacy. Thirty years have nearly elapsed since it was written, and in the interval our population, our wealth, our territorial extension, our power--physical and moral--have nearly trebled. Reasoning upon this state of things from the sound and judicious principles of Washington, must we not say that the period which he predicted as then not far off has arrived; that America has a set of primary interests which have none or a remote relation to Europe; that the interference of Europe, therefore, in those concerns should be spontaneously withheld by her upon the same principles that we have never interfered with hers, and that if she should interfere, as she may, by measures which may have a great and dangerous recoil upon ourselves, we might be called in defense of our own altars and firesides to take an attitude which would cause our neutrality to be respected, and choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by justice, should counsel.

The acceptance of this invitation, therefore, far from conflicting with the counsel or the policy of Washington, is directly deducible from and conformable to it. Nor is it less conformable to the views of my immediate predecessor as declared in his annual message to Congress of the 2d December, 1823, to which I have already adverted, and to an important passage of which I invite the attention of the House:

The citizens of the United States (said he) cherish sentiments the most friendly in favor of the liberty and happiness of their fellow-men on that (the European) side of the Atlantic. In the wars of the European powers in matters relating to themselves we have never taken any part, nor does it comport with our policy so to do. It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we are of necessity more immediately connected, and by causes which must be obvious to all enlightened and impartial observers. The political system of the allied powers is essentially different in this respect from that of America. This difference proceeds from that which exists in their respective Governments. And to the defense of our own, which has been achieved by the loss of so much blood and treasure, and matured by the wisdom of their most enlightened citizens, and under which we have enjoyed unexampled felicity, this whole nation is devoted. We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations subsisting between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere; but with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintained it, and whose independence we have on great consideration and on just principles acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purposes of oppressing them or controlling in any other manner their destiny by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States. In the war between those new Governments and Spain we declared our neutrality at the time of their recognition, and to this we have adhered and shall continue to adhere, provided no change shall occur which in the judgment of the competent authorities of this Government shall make a corresponding change on the part of the United States indispensable to their security.

To the question which may be asked, whether this meeting and the principles which may be adjusted and settled by it as rules of intercourse between the American nations may not give umbrage to the holy league of European powers or offense to Spain, it is deemed a sufficient answer that our attendance at Panama can give no just cause of umbrage or offense to either, and that the United States will stipulate nothing there which can give such cause. Here the right of inquiry into our purposes and measures must stop. The holy league of Europe itself was formed without inquiring of the United States whether it would or would not give umbrage to them. The fear of giving umbrage to the holy league of Europe was urged as a motive for denying to the American nations the acknowledgment of their independence. That it would be viewed by Spain as hostility to her was not only urged, but directly declared by herself. The Congress and Administration of that day consulted their rights and duties, and not their fears. Fully determined to give no needless displeasure to any foreign power, the United States can estimate the probability of their giving it only by the right which any foreign state could have to take it from their measures. Neither the representation of the United States at Panama nor any measure to which their assent may be yielded there will give to the holy league or any of its members, nor to Spain, the right to take offense; for the rest the United States must still, as heretofore, take counsel from their duties rather than their fears.

Such are the objects in which it is expected that the plenipotentiaries of the United States, when commissioned to attend the meeting at the Isthmus, will take part, and such are the motives and purposes with which the invitation of the three Republics was accepted. It was, however, as the House will perceive from the correspondence, accepted only upon condition that the nomination of commissioners for the mission should receive the advice and consent of the Senate.

The concurrence of the House to the measure by the appropriations necessary for carrying it into effect is alike subject to its free determination and indispensable to the fulfillment of the intention.

That the congress at Panama will accomplish all, or even any, of the transcendent benefits to the human race which warmed the conceptions of its first proposer it were perhaps indulging too sanguine a forecast of events to promise. It is in its nature a measure speculative and experimental. The blessing of Heaven may turn it to the account of human improvement; accidents unforeseen and mischances not to be anticipated may baffle all its high purposes and disappoint its fairest expectations. But the design is great, is benevolent, is humane.

It looks to the melioration of the condition of man. It is congenial with that spirit which prompted the declaration of our independence, which inspired the preamble of our first treaty with France, which dictated our first treaty with Prussia and the instructions under which it was negotiated, which filled the hearts and fired the souls of the immortal founders of our Revolution.

With this unrestricted exposition of the motives by which I have been governed in this transaction, as well as of the objects to be discussed and of the ends, if possible, to be attained by our representation at the proposed congress, I submit the propriety of an appropriation to the candid consideration and enlightened patriotism of the Legislature.

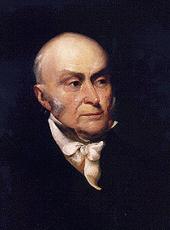

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS.

John Quincy Adams, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/207536