U.S. Ambassador to Brazil John J. Danilovich. Mr. President, Secretary Rice, fellow Brazilians, I'd like to thank you all for being here this morning. It's a pleasure for us to welcome you here on this beautiful Sunday morning in Brasilia.

Brazil is a land of promise, of enormous potential, and of great possibilities. And the promise, potential, and possibilities of Brazil are perhaps no more visible than in yourselves. I want to thank you for the opportunity of the President and the Secretary, of meeting with you today. To a large extent, the future of your country lies in your hands, and the President looks forward to discussing things of relevance to Brazil and the United States and our important bilateral relationship. And with that being said, I'd like to turn the——

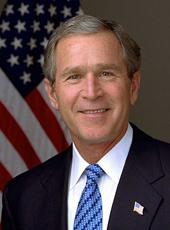

The President. John, let me say something. The Ambassador is trying to cull me out of the conversation early on. [Laughter] Listen, thank you for coming. First, I am here because I want to send a very clear signal to the people of Brazil that the relationship between America and Brazil is an important relationship, that Brazil is a friend, and that Brazil has got an important part of working with America to bring prosperity to not only our own citizens but to help others as well and by doing so, kind of lay the—lay conditions for a peaceful continent.

It's in our interests that our neighborhood be a prosperous neighborhood. It's in our interests that we work with the largest country in the neighborhood. And so I come to not only discuss philosophy and points of view with you but also to meet with President Lula, with whom I've got a good relationship.

He is a person who had to make some tough decisions. That's what leaders have to do; you've got to make tough decisions. And he's made hard decisions for the people of Brazil. He is—the economy is going well here, which is good news. He also has got a good heart. And I share the same concern he has; I share a concern of making sure that the least fortunate among us has a chance to survive and succeed.

And so this is going to be a good trip here, and I'm grateful for you all taking time to come by and visit. I look forward to having a fruitful discussion with you. And we'll start with Carlos.

Participant. Thank you very much, Mr. President. Latin Americans for a long time have had a love-hatred relationship with the U.S. Latin Americans admire the military and economic power of the United States, its popular culture, and many values with which they share. But Latin Americans resist the somewhat missionary nature of U.S. when justifying its international actions— for instance, when the U.S. exports democracy, exports market economies, or even exports civil liberties. This has been really very much criticized or contested, even in this region of the world. The Mar del Plata incidents of a few days ago, during the Summit of the Americas, showed that the mood of the demonstrators may easily go beyond the acceptable limits in—civilization.

My question now: Is the U.S. able to pinpoint the causes for these disagreements that they have with the opinionmakers here in Latin America, and does the U.S. have a clear strategy to change this love and hatred relationship into one of cooperation and friendship?

The President. Well, first of all, I—we met in a society which allows people to express their different points of view. In other words—which is positive—I expect there to be dissent. That's what freedom is all about. People should be allowed to express themselves. And so what happened in Argentina happens in America. That's positive. Can you imagine being in a society where people were not allowed to express their positions?

Secondly, I fully understand there's, at times, a view of America that is, in my opinion, not an accurate view. I mean, you say, "missionary zeal to spread democracy"—I do have a deep desire to help others assume a democracy that is a democracy that conforms to their traditions and their customs. And the reason why is because the world has seen that democracies do not fight each other.

As an example, war broke out in Europe in the early 1900s, as well as the mid-1900s. And yet we've had no war in Europe since. And one of the reasons why is because the nations of Europe became democracies, not American democracy but democracies that reflected the values of the people in that country—in their countries.

One of the stories I like to share with people—it's an interesting story, and I think an illustration of what I'm trying to do—is that Japan was the sworn enemy of the United States in the late 1940s. My dad was a soldier, Navy pilot, and fighting the Japanese. Today—I'm going to Japan in 2 weeks. I will be sitting down with one of the best friends that I have in the international arena, Koizumi. That's interesting, isn't it? What happened between the time when America was fighting Japan and when, now, Japan is an ally with the United States in dealing with a tyrant in North Korea, for example? And what happened was, Japan adopted a Japanese-style democracy.

And so I am anxious to work with countries to help make sure that the institutions, universal institutions of democracy become entrenched in society: freedom to worship, freedom of the press, rule of law.

I will also tell you, I firmly believe that a society which is democratic is one much more likely to be able to deal with the social ills of a society. I mean, a democracy is one in which minorities have rights and can express themselves through the legislative process. Tyrannies are such that minorities don't have rights, unless you happen to be aligned with the tyrant.

And so, one, I don't think America, nor Brazil, should ever back down from believing in the universality of freedom and democracy. Secondly, I hope that I am able to do so in a way that explains our position, as opposed to alienating people. And one of the reasons I've come to Brazil is to make that eminently clear, that the United States is a friend of Brazil and that our values that we discuss are universal in nature. They apply to Brazil equally as they apply to America.

So very good question, Carlos.

NOTE: The President spoke at 9:54 a.m. at the U.S. Embassy. In his remarks, he referred to President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of Brazil; Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi of Japan; and Chairman Kim Chong-il of North Korea. The participant spoke in Portuguese, and his remarks were translated by an interpreter. The Office of the Press Secretary also released a Spanish language transcript of these remarks. A portion of these remarks could not be verified because the tape was incomplete.

George W. Bush, Remarks in a Discussion With Young Leaders in Brasilia, Brazil Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/214443