To the Senate of the United States:

It appears by the published Journal of the Senate that on the 26th of December last a resolution was offered by a member of the Senate, which after a protracted debate was on the 28th day of March last modified by the mover and passed by the votes of twenty-six Senators out of forty-six who were present and voted, in the following words, viz:

Resolved , That the President, in the late Executive proceedings in relation to the public revenue, has assumed upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws, but in derogation of both.

Having had the honor, through the voluntary suffrages of the American people, to fill the office of President of the United States during the period which may be presumed to have been referred to in this resolution, it is sufficiently evident that the censure it inflicts was intended for myself. Without notice, unheard and untried, I thus find myself charged on the records of the Senate, and in a form hitherto unknown in our history, with the high crime of violating the laws and Constitution of my country.

It can seldom be necessary for any department of the Government, when assailed in conversation or debate or by the strictures of the press or of popular assemblies, to step out of its ordinary path for the purpose of vindicating its conduct or of pointing out any irregularity or injustice in the manner of the attack; but when the Chief Executive Magistrate is, by one of the most important branches of the Government in its official capacity, in a public manner, and by its recorded sentence, but without precedent, competent authority, or just cause, declared guilty of a breach of the laws and Constitution, it is due to his station, to public opinion, and to a proper self-respect that the officer thus denounced should promptly expose the wrong which has been done.

In the present case, moreover, there is even a stronger necessity for such a vindication. By an express provision of the Constitution, before the President of the United States can enter on the execution of his office he is required to take an oath or affirmation in the following words:

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States and will to the best of my ability preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.

The duty of defending so far as in him lies the integrity of the Constitution would indeed have resulted from the very nature of his office, but by thus expressing it in the official oath or affirmation, which in this respect differs from that of any other functionary, the founders of our Republic have attested their sense of its importance and have given to it a peculiar solemnity and force. Bound to the performance of this duty by the oath I have taken, by the strongest obligations of gratitude to the American people, and by the ties which unite my every earthly interest with the welfare and glory of my country, and perfectly convinced that the discussion and passage of the above-mentioned resolution were not only unauthorized by the Constitution, but in many respects repugnant to its provisions and subversive of the rights secured by it to other coordinate departments, I deem it an imperative duty to maintain the supremacy of that sacred instrument and the immunities of the department intrusted to my care by all means consistent with my own lawful powers, with the rights of others, and with the genius of our civil institutions. To this end I have caused this my solemn protest against the aforesaid proceedings to be placed on the files of the executive department and to be transmitted to the Senate.

It is alike due to the subject, the Senate, and the people that the views which I have taken of the proceedings referred to, and which compel me to regard them in the light that has been mentioned, should be exhibited at length, and with the freedom and firmness which are required by an occasion so unprecedented and peculiar.

Under the Constitution of the United States the powers and functions of the various departments of the Federal Government and their responsibilities for violation or neglect of duty are clearly defined or result by necessary inference. The legislative power is, subject to the qualified negative of the President, vested in the Congress of the United States, composed of the Senate and House of Representatives; the executive power is vested exclusively in the President, except that in the conclusion of treaties and in certain appointments to office he is to act with the advice and consent of the Senate; the judicial power is vested exclusively in the Supreme and other courts of the United States, except in cases of impeachment, for which purpose the accusatory power is vested in the House of Representatives and that of hearing and determining in the Senate. But although for the special purposes which have been mentioned there is an occasional intermixture of the powers of the different departments, yet with these exceptions each of the three great departments is independent of the others in its sphere of action, and when it deviates from that sphere is not responsible to the others further than it is expressly made so in the Constitution. In every other respect each of them is the coequal of the other two, and all are the servants of the American people, without power or right to control or censure each other in the service of their common superior, save only in the manner and to the degree which that superior has prescribed.

The responsibilities of the President are numerous and weighty. He is liable to impeachment for high crimes and misdemeanors, and on due conviction to removal from office and perpetual disqualification; and notwithstanding such conviction, he may also be indicted and punished according to law. He is also liable to the private action of any party who may have been injured by his illegal mandates or instructions in the same manner and to the same extent as the humblest functionary. In addition to the responsibilities which may thus be enforced by impeachment, criminal prosecution, or suit at law, he is also accountable at the bar of public opinion for every act of his Administration. Subject only to the restraints of truth and justice, the free people of the United States have the undoubted right, as individuals or collectively, orally or in writing, at such times and in such language and form as they may think proper, to discuss his official conduct and to express and promulgate their opinions concerning it. Indirectly also his conduct may come under review in either branch of the Legislature, or in the Senate when acting in its executive capacity, and so far as the executive or legislative proceedings of these bodies may require it, it may be exercised by them. These are believed to be the proper and only modes in which the President of the United States is to be held accountable for his official conduct.

Tested by these principles, the resolution of the Senate is wholly unauthorized by the Constitution, and in derogation of its entire spirit. It assumes that a single branch of the legislative department may for the purposes of a public censure, and without any view to legislation or impeachment, take up, consider, and decide upon the official acts of the Executive. But in no part of the Constitution is the President subjected to any such responsibility, and in no part of that instrument is any such power conferred on either branch of the Legislature.

The justice of these conclusions will be illustrated and confirmed by a brief analysis of the powers of the Senate and a comparison of their recent proceedings with those powers.

The high functions assigned by the Constitution to the Senate are in their nature either legislative, executive, or judicial. It is only in the exercise of its judicial powers, when sitting as a court for the trial of impeachments, that the Senate is expressly authorized and necessarily required to consider and decide upon the conduct of the President or any other public officer. Indirectly, however, as has already been suggested, it may frequently be called on to perform that office. Cases may occur in the course of its legislative or executive proceedings in which it may be indispensable to the proper exercise of its powers that it should inquire into and decide upon the conduct of the President or other public officers, and in every such case its constitutional right to do so is cheerfully conceded. But to authorize the Senate to enter on such a task in its legislative or executive capacity the inquiry must actually grow out of and tend to some legislative or executive action, and the decision, when expressed, must take the form of some appropriate legislative or executive act.

The resolution in question was introduced, discussed, and passed not as a joint but as a separate resolution. It asserts no legislative power, proposes no legislative action, and neither possesses the form nor any of the attributes of a legislative measure. It does not appear to have been entertained or passed with any view or expectation of its issuing in a law or joint resolution, or in the repeal of any law or joint resolution, or in any other legislative action.

Whilst wanting both the form and substance of a legislative measure, it is equally manifest that the resolution was not justified by any of the executive powers conferred on the Senate. These powers relate exclusively to the consideration of treaties and nominations to office, and they are exercised in secret session and with closed doors. This resolution does not apply to any treaty or nomination, and was passed in a public session.

Nor does this proceeding in any way belong to that class of incidental resolutions which relate to the officers of the Senate, to their Chamber and other appurtenances, or to subjects of order and other matters of the like nature, in all which either House may lawfully proceed without any cooperation with the other or with the President.

On the contrary, the whole phraseology and sense of the resolution seem to be judicial. Its essence, true character, and only practical effect are to be found in the conduct which it enlarges upon the President and in the judgment which it pronounces on that conduct. The resolution, therefore though discussed and adopted by the Senate in its legislative capacity, is in its office and in all its characteristics essentially judicial.

That the Senate possesses a high judicial power and that instances may occur in which the President of the United States will be amenable to it is undeniable; but under the provisions of the Constitution it would seem to be equally plain that neither the President nor any other officer can be rightfully subjected to the operation of the judicial power of the Senate except in the cases and under the forms prescribed by the Constitution.

The Constitution declares that "the President, Vice-President, and all civil officers of the United States shall be removed from office on impeachment for and conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors;" that the House of Representatives "shall have the sole power of impeachment;" that the Senate "shall have the sole power to try all impeachments;" that "when sitting for that purpose they shall be on oath or affirmation;" that "when the President of the United States is tried the Chief Justice shall preside;" that "no person shall be convicted without the concurrence of two-thirds of the members present," and that "judgment shall not extend further than to removal from office and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust, or profit under the United States."

The resolution above quoted charges, in substance, that in certain proceedings relating to the public revenue the President has usurped authority and power not conferred upon him by the Constitution and laws, and that in doing so he violated both. Any such act constitutes a high crime--one of the highest, indeed, which the President can commit--a crime which justly exposes him to impeachment by the House of Representatives, and, upon due conviction, to removal from office and to the complete and immutable disfranchisement prescribed by the Constitution. The resolution, then, was in substance an impeachment of the President, and in its passage amounts to a declaration by a majority of the Senate that he is guilty of an impeachable offense. As such it is spread upon the journals of the Senate, published to the nation and to the world, made part of our enduring archives, and incorporated in the history of the age. The punishment of removal from office and future disqualification does not, it is true, follow this decision, nor would it have followed the like decision if the regular forms of proceeding had been pursued, because the requisite number did not concur in the result. But the moral influence of a solemn declaration by a majority of the Senate that the accused is guilty of the offense charged upon him has been as effectually secured as if the like declaration had been made upon an impeachment expressed in the same terms. Indeed, a greater practical effect has been gained, because the votes given for the resolution, though not sufficient to authorize a judgment of guilty on an impeachment, were numerous enough to carry that resolution.

That the resolution does not expressly allege that the assumption of power and authority which it condemns was intentional and corrupt is no answer to the preceding view of its character and effect. The act thus condemned necessarily implies volition and design in the individual to whom it is imputed, and, being unlawful in its character, the legal conclusion is that it was prompted by improper motives and committed with an unlawful intent. The charge is not of a mistake in the exercise of supposed powers, but of the assumption of powers not conferred by the Constitution and laws, but in derogation of both, and nothing is suggested to excuse or palliate the turpitude of the act. In the absence of any such excuse or palliation there is only room for one inference, and that is that the intent was unlawful and corrupt. Besides, the resolution not only contains no mitigating suggestions, but, on the contrary, it holds up the act complained of as justly obnoxious to censure and reprobation, and thus as distinctly stamps it with impurity of motive as if the strongest epithets had been used.

The President of the United States, therefore, has been by a majority of his constitutional triers accused and found guilty of an impeachable offense, but in no part of this proceeding have the directions of the Constitution been observed.

The impeachment, instead of being preferred and prosecuted by the House of Representatives, originated in the Senate, and was prosecuted without the aid or concurrence of the other House. The oath or affirmation prescribed by the Constitution was not taken by the Senators, the Chief Justice did not preside, no notice of the charge was given to the accused, and no opportunity afforded him to respond to the accusation, to meet his accusers face to face, to cross-examine the witnesses, to procure counteracting testimony, or to be heard in his defense. The safeguards and formalities which the Constitution has connected with the power of impeachment were doubtless supposed by the framers of that instrument to be essential to the protection of the public servant, to the attainment of justice, and to the order, impartiality, and dignity of the procedure. These safeguards and formalities were not only practically disregarded in the commencement and conduct of these proceedings, but in their result I find myself convicted by less than two-thirds of the members present of an impeachable offense.

In vain may it be alleged in defense of this proceeding that the form of the resolution is not that of an impeachment or of a judgment thereupon, that the punishment prescribed in the Constitution does not follow its adoption, or that in this case no impeachment is to be expected from the House of Representatives. It is because it did not assume the form of an impeachment that it is the more palpably repugnant to the Constitution, for it is through that form only that the President is judicially responsible to the Senate; and though neither removal from office nor future disqualification ensues, yet it is not to be presumed that the framers of the Constitution considered either or both of those results as constituting the whole of the punishment they prescribed. The judgment of guilty by the highest tribunal in the Union, the stigma it would inflict on the offender, his family, and fame, and the perpetual record on the Journal, handing down to future generations the story of his disgrace, were doubtless regarded by them as the bitterest portions, if not the very essence, of that punishment. So far, therefore, as some of its most material parts are concerned, the passage, recording, and promulgation of the resolution are an attempt to bring them on the President in a manner unauthorized by the Constitution. To shield him and other officers who are liable to impeachment from consequences so momentous, except when really merited by official delinquencies, the Constitution has most carefully guarded the whole process of impeachment. A majority of the House of Representatives must think the officer guilty before he can be charged. Two-thirds of the Senate must pronounce him guilty or he is deemed to be innocent. Forty-six Senators appear by the Journal to have been present when the vote on the resolution was taken. If after all the solemnities of an impeachment, thirty of those Senators had voted that the President was guilty, yet would he have been acquitted; but by the mode of proceeding adopted in the present case a lasting record of conviction has been entered up by the votes of twenty-six Senators without an impeachment or trial, whilst the Constitution expressly declares that to the entry of such a judgment an accusation by the House of Representatives, a trial by the Senate, and a concurrence of two-thirds in the vote of guilty shall be indispensable prerequisites.

Whether or not an impeachment was to be expected from the House of Representatives was a point on which the Senate had no constitutional right to speculate, and in respect to which, even had it possessed the spirit of prophecy, its anticipations would have furnished no just ground for this procedure. Admitting that there was reason to believe that a violation of the Constitution and laws had been actually committed by the President, still it was the duty of the Senate, as his sole constitutional judges, to wait for an impeachment until the other House should think proper to prefer it. The members of the Senate could have no right to infer that no impeachment was intended. On the contrary, every legal and rational presumption on their part ought to have been that if there was good reason to believe him guilty of an impeachable offense the House of Representatives would perform its constitutional duty by arraigning the offender before the justice of his country. The contrary presumption would involve an implication derogatory to the integrity and honor of the representatives of the people. But suppose the suspicion thus implied were actually entertained and for good cause, how can it justify the assumption by the Senate of powers not conferred by the Constitution?

It is only necessary to look at the condition in which the Senate and the President have been placed by this proceeding to perceive its utter incompatibility with the provisions and the spirit of the Constitution and with the plainest dictates of humanity and justice.

If the House of Representatives shall be of opinion that there is just ground for the censure pronounced upon the President, then will it be the solemn duty of that House to prefer the proper accusation and to cause him to be brought to trial by the constitutional tribunal. But in what condition would he find that tribunal? A majority of its members have already considered the case, and have not only formed but expressed a deliberate judgment upon its merits. It is the policy of our benign systems of jurisprudence to secure in all criminal proceedings, and even in the most trivial litigations, a fair, unprejudiced, and impartial trial, and surely it can not be less important that such a trial should be secured to the highest officer of the Government.

The Constitution makes the House of Representatives the exclusive judges, in the first instance, of the question whether the President has committed an impeachable offense. A majority of the Senate, whose interference with this preliminary question has for the best of all reasons been studiously excluded, anticipate the action of the House of Representatives, assume not only the function which belongs exclusively to that body, but convert themselves into accusers, witnesses, counsel, and judges, and prejudge the whole case, thus presenting the appalling spectacle in a free State of judges going through a labored preparation for an impartial hearing and decision by a previous ex parte investigation and sentence against the supposed offender.

There is no more settled axiom in that Government whence we derived the model of this part of our Constitution than that "the lords can not impeach any to themselves, nor join in the accusation, because they are judges." Independently of the general reasons on which this rule is founded, its propriety and importance are greatly increased by the nature of the impeaching power. The power of arraigning the high officers of government before a tribunal whose sentence may expel them from their seats and brand them as infamous is eminently a popular remedy--a remedy designed to be employed for the protection of private right and public liberty against the abuses of injustice and the encroachments of arbitrary power. But the framers of the Constitution were also undoubtedly aware that this formidable instrument had been and might be abused, and that from its very nature an impeachment for high crimes and misdemeanors, whatever might be its result, would in most cases be accompanied by so much of dishonor and reproach, solicitude and suffering, as to make the power of preferring it one of the highest solemnity and importance. It was due to both these considerations that the impeaching power should be lodged in the hands of those who from the mode of their election and the tenure of their offices would most accurately express the popular will and at the same time be most directly and speedily amenable to the people. The theory of these wise and benignant intentions is in the present case effectually defeated by the proceedings of the Senate. The members of that body represent not the people, but the States; and though they are undoubtedly responsible to the States, yet from their extended term of service the effect of that responsibility during the whole period of that term must very much depend upon their own impressions of its obligatory force. When a body thus constituted expresses beforehand its opinion in a particular case, and thus indirectly invites a prosecution, it not only assumes a power intended for wise reasons to be confined to others, but it shields the latter from that exclusive and personal responsibility under which it was intended to be exercised, and reverses the whole scheme of this part of the Constitution.

Such would be some of the objections to this procedure, even if it were admitted that there is just ground for imputing to the President the offenses charged in the resolution. But if, on the other hand, the House of Representatives shall be of opinion that there is no reason for charging them upon him, and shall therefore deem it improper to prefer an impeachment, then will the violation of privilege as it respects that House, of justice as it regards the President, and of the Constitution as it relates to both be only the more conspicuous and impressive.

The constitutional mode of procedure on an impeachment has not only been wholly disregarded, but some of the first principles of natural right and enlightened jurisprudence have been violated in the very form of the resolution. It carefully abstains from averring in which of "the late proceedings in relation to the public revenue the President has assumed upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws." It carefully abstains from specifying what laws or what parts of the Constitution have been violated. Why was not the certainty of the offense--" the nature and cause of the accusation "--set out in the manner required in the Constitution before even the humblest individual, for the smallest crime, can be exposed to condemnation? Such a specification was due to the accused that he might direct his defense to the real points of attack, to the people that they might clearly understand in what particulars their institutions had been violated, and to the truth and certainty of our public annals. As the record now stands, whilst the resolution plainly charges upon the President at least one act of usurpation in "the late Executive proceedings in relation to the public revenue," and is so framed that those Senators who believed that one such act, and only one, had been committed could assent to it, its language is yet broad enough to include several such acts, and so it may have been regarded by some of those who voted for it. But though the accusation is thus comprehensive in the censures it implies, there is no such certainty of time, place, or circumstance as to exhibit the particular conclusion of fact or law which induced any one Senator to vote for it; and it may well have happened that whilst one Senator believed that some particular act embraced in the resolution was an arbitrary and unconstitutional assumption of power, others of the majority may have deemed that very act both constitutional and expedient, or, if not expedient, yet still within the pale of the Constitution; and thus a majority of the Senators may have been enabled to concur in a vague and undefined accusation that the President, in the course of "the late Executive proceedings in relation to the public revenue," had violated the Constitution and laws, whilst if a separate vote had been taken in respect to each particular act included within the general terms the accusers of the President might on any such vote have been found in the minority.

Still further to exemplify this feature of the proceeding, it is important to be remarked that the resolution as originally offered to the Senate specified with adequate precision certain acts of the President which it denounced as a violation of the Constitution and laws, and that it was not until the very close of the debate, and when perhaps it was apprehended that a majority might not sustain the specific accusation contained in it, that the resolution was so modified as to assume its present form. A more striking illustration of the soundness and necessity of the rules which forbid vague and indefinite generalities and require a reasonable certainty in all judicial allegations, and a more glaring instance of the violation of those rules, has seldom been exhibited.

In this view of the resolution it must certainly be regarded not as a vindication of any particular provision of the law or the Constitution, but simply as an official rebuke or condemnatory sentence, too general and indefinite to be easily repelled, but yet sufficiently precise to bring into discredit the conduct and motives of the Executive. But whatever it may have been intended to accomplish, it is obvious that the vague, general, and abstract form of the resolution is in perfect keeping with those other departures from first principles and settled improvements in jurisprudence so properly the boast of free countries in modern times. And it is not too much to say of the whole of these proceedings that if they shall be approved and sustained by an intelligent people, then will that great contest with arbitrary power which had established in statutes, in bills of rights, in sacred charters, and in constitutions of government the right of every citizen to a notice before trial, to a bearing before conviction, and to an impartial tribunal for deciding on the charge have been waged in vain.

If the resolution had been left in its original form it is not to be presumed that it could ever have received the assent of a majority of the Senate, for the acts therein specified as violations of the Constitution and laws were clearly within the limits of the Executive authority. They are the "dismissing the late Secretary of the Treasury because he would not, contrary to his sense of his own duty, remove the money of the United States in deposit with the Bank of the United States and its branches in conformity with the President's opinion, and appointing his successor to effect such removal, which has been done." But as no other specification has been substituted, and as these were the "Executive proceedings in relation to the public revenue" principally referred to in the course of the discussion, they will doubtless be generally regarded as the acts intended to be denounced as "an assumption of authority and power not conferred by the Constitution or laws, but in derogation of both." It is therefore due to the occasion that a condensed summary of the views of the Executive in respect to them should be here exhibited.

By the Constitution "the executive power is vested in a President of the United States." Among the duties imposed upon him, and which he is sworn to perform, is that of "taking care that the laws be faithfully executed." Being thus made responsible for the entire action of the executive department, it was but reasonable that the power of appointing, overseeing, and controlling those who execute the laws--a power in its nature executive--should remain in his hands. It is therefore not only his right, but the Constitution makes it his duty, to "nominate and, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint" all "officers of the United States whose appointments are not in the Constitution otherwise provided for," with a proviso that the appointment of inferior officers may be vested in the President alone, in the courts of justice, or in the heads of Departments.

The executive power vested in the Senate is neither that of "nominating" nor "appointing." It is merely a check upon the Executive power of appointment. If individuals are proposed for appointment by the President by them deemed incompetent or unworthy, they may withhold their consent and the appointment can not be made. They check the action of the Executive, but can not in relation to those very subjects act themselves nor direct him. Selections are still made by the President, and the negative given to the Senate, without diminishing his responsibility, furnishes an additional guaranty to the country that the subordinate executive as well as the judicial offices shall be filled with worthy and competent men.

The whole executive power being vested in the President, who is responsible for its exercise, it is a necessary consequence that he should have a right to employ agents of his own choice to aid him in the performance of his duties, and to discharge them when he is no longer willing to be responsible for their acts. In strict accordance with this principle, the power of removal, which, like that of appointment, is an original executive power, is left unchecked by the Constitution in relation to all executive officers, for whose conduct the President is responsible, while it is taken from him in relation to judicial officers, for whose acts he is not responsible. In the Government from which many of the fundamental principles of our system are derived the head of the executive department originally had power to appoint and remove at will all officers, executive and judicial. It was to take the judges out of this general power of removal, and thus make them independent of the Executive, that the tenure of their offices was changed to good behavior. Nor is it conceivable why they are placed in our Constitution upon a tenure different from that of all other officers appointed by the Executive unless it be for the same purpose.

But if there were any just ground for doubt on the face of the Constitution whether all executive officers are removable at the will of the President, it is obviated by the contemporaneous construction of the instrument and the uniform practice under it.

The power of removal was a topic of solemn debate in the Congress of 1789 while organizing the administrative departments of the Government, and it was finally decided that the President derived from the Constitution the power of removal so far as it regards that department for whose acts he is responsible. Although the debate covered the whole ground, embracing the Treasury as well as all the other Executive Departments, it arose on a motion to strike out of the bill to establish a Department of Foreign Affairs, since called the Department of State, a clause declaring the Secretary "to be removable from office by the President of the United States." After that motion had been decided in the negative it was perceived that these words did not convey the sense of the House of Representatives in relation to the true source of the power of removal. With the avowed object of preventing any future inference that this power was exercised by the President in virtue of a grant from Congress, when in fact that body considered it as derived from the Constitution, the words which had been the subject of debate were struck out, and in lieu thereof a clause was inserted in a provision concerning the chief clerk of the Department, which declared that "whenever the said principal officer shall be removed from office by the President of the United States, or in any other case of vacancy," the chief clerk should during such vacancy have charge of the papers of the office. This change having been made for the express purpose of declaring the sense of Congress that the President derived the power of removal from the Constitution, the act as it passed has always been considered as a full expression of the sense of the legislature on this important part of the American Constitution.

Here, then, we have the concurrent authority of President Washington, of the Senate, and the House of Representatives, numbers of whom had taken an active part in the convention which framed the Constitution and in the State conventions which adopted it, that the President derived an unqualified power of removal from that instrument itself, which is "beyond the reach of legislative authority." Upon this principle the Government has now been steadily administered for about forty-five years, during which there have been numerous removals made by the President or by his direction, embracing every grade of executive officers from the heads of Departments to the messengers of bureaus.

The Treasury Department in the discussions of 1789 was considered on the same footing as the other Executive Departments, and in the act establishing it were incorporated the precise words indicative of the sense of Congress that the President derives his power to remove the Secretary from the Constitution, which appear in the act establishing the Department of Foreign Affairs. An Assistant Secretary of the Treasury was created, and it was provided that he should take charge of the books and papers of the Department "whenever the Secretary shall be removed from office by the President of the United States." The Secretary of the Treasury being appointed by the President, and being considered as constitutionally removable by him, it appears never to have occurred to anyone in the Congress of 1789, or since until very recently, that he was other than an executive officer, the mere instrument of the Chief Magistrate in the execution of the laws, subject, like all other heads of Departments, to his supervision and control. No such idea as an officer of the Congress can be found in the Constitution or appears to have suggested itself to those who organized the Government. There are officers of each House the appointment of which is authorized by the Constitution, but all officers referred to in that instrument as coming within the appointing power of the President, whether established thereby or created by law, are "officers of the United States." No joint power of appointment is given to the two Houses of Congress, nor is there any accountability to them as one body; but as soon as any office is created by law, of whatever name or character, the appointment of the person or persons to fill it devolves by the Constitution upon the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate, unless it be an inferior office, and the appointment be vested by the law itself "in the President alone, in the courts of law, or in the heads of Departments."

But at the time of the organization of the Treasury Department an incident occurred which distinctly evinces the unanimous concurrence of the First Congress in the principle that the Treasury Department is wholly executive in its character and responsibilities. A motion was made to strike out the provision of the bill making it the duty of the Secretary "to digest and report plans for the improvement and management of the revenue and for the support of public credit," on the ground that it would give the executive department of the Government too much influence and power in Congress. The motion was not opposed on the ground that the Secretary was the officer of Congress and responsible to that body, which would have been conclusive if admitted, but on other ground, which conceded his executive character throughout. The whole discussion evinces an unanimous concurrence in the principle that the Secretary of the Treasury is wholly an executive officer, and the struggle of the minority was to restrict his power as such. From that time down to the present the Secretary of the Treasury, the Treasurer, Register, Comptrollers, Auditors, and clerks who fill the offices of that Department have in the practice of the Government been considered and treated as on the same footing with corresponding grades of officers in all the other Executive Departments.

The custody of the public property, under such regulations as may be prescribed by legislative authority, has always been considered an appropriate function of the executive department in this and all other Governments. In accordance with this principle, every species of property belonging to the United States (excepting that which is in the use of the several coordinate departments of the Government as means to aid them in performing their appropriate functions) is in charge of officers appointed by the President, whether it be lands, or buildings, or merchandise, or provisions, or clothing, or arms and munitions of war. The superintendents and keepers of the whole are appointed by the President, responsible to him, and removable at his will.

Public money is but a species of public property. It can not be raised by taxation or customs, nor brought into the Treasury in any other way except by law; but whenever or howsoever obtained, its custody always has been and always must be, unless the Constitution be changed, intrusted to the executive department. No officer can be created by Congress for the purpose of taking charge of it whose appointment would not by the Constitution at once devolve on the President and who would not be responsible to him for the faithful performance of his duties. The legislative power may undoubtedly bind him and the President by any laws they may think proper to enact; they may prescribe in what place particular portions of the public property shall be kept and for what reason it shall be removed, as they may direct that supplies for the Army or Navy shall be kept in particular stores, and it will be the duty of the President to see that the law is faithfully executed; yet will the custody remain in the executive department of the Government. Were the Congress to assume, with or without a legislative act, the power of appointing officers, independently of the President, to take the charge and custody of the public property contained in the military and naval arsenals, magazines, and storehouses, it is believed that such an act would be regarded by all as a palpable usurpation of executive power, subversive of the form as well as the fundamental principles of our Government. But where is the difference in principle whether the public property be in the form of arms, munitions of war, and supplies or in gold and silver or bank notes? None can be perceived; none is believed to exist. Congress can not, therefore, take out of the hands of the executive department the custody of the public property or money without an assumption of executive power and a subversion of the first principles of the Constitution.

The Congress of the United States have never passed an act imperatively directing that the public moneys shall be kept in any particular place or places. From the origin of the Government to the year 1816 the statute book was wholly silent on the subject. In 1789 a Treasurer was created, subordinate to the Secretary of the Treasury, and through him to the President. He was required to give bond safely to keep and faithfully to disburse the public moneys, without any direction as to the manner or places in which they should be kept. By reference to the practice of the Government it is found that from its first organization the Secretary of the Treasury, acting under the supervision of the President, designated the places in which the public moneys should be kept, and especially directed all transfers from place to place. This practice was continued, with the silent acquiescence of Congress, from 1789 down to 1816, and although many banks were selected and discharged, and although a portion of the moneys were first placed in the State banks, and then in the former Bank of the United States, and upon the dissolution of that were again transferred to the State banks, no legislation was thought necessary by Congress, and all the operations were originated and perfected by Executive authority. The Secretary of the Treasury, responsible to the President, and with his approbation, made contracts and arrangements in relation to the whole subject-matter, which was thus entirely committed to the direction of the President under his responsibilities to the American people and to those who were authorized to impeach and punish him for any breach of this important trust.

The act of 1816 establishing the Bank of the United States directed the deposits of public money to be made in that bank and its branches in places in which the said bank and branches thereof may be established, "unless the Secretary of the Treasury should otherwise order and direct," in which event he was required to give his reasons to Congress. This was but a continuation of his preexisting power as the head of an Executive Department to direct where the deposits should be made, with the superadded obligation of giving his reasons to Congress for making them elsewhere than in the Bank of the United States and its branches. It is not to be considered that this provision in any degree altered the relation between the Secretary of the Treasury and the President as the responsible head of the executive department, or released the latter from his constitutional obligation to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed." On the contrary, it increased his responsibilities by adding another to the long list of laws which it was his duty to carry into effect.

It would be an extraordinary result if because the person charged by law with a public duty is one of his Secretaries it were less the duty of the President to see that law faithfully executed than other laws enjoining duties upon subordinate officers or private citizens. If there be any difference, it would seem that the obligation is the stronger in relation to the former, because the neglect is in his presence and the remedy at hand.

It can not be doubted that it was the legal duty of the Secretary of the Treasury to order and direct the deposits of the public money to be made elsewhere than in the Bank of the United States whenever sufficient reasons existed for making the change. If in such a case he neglected or refused to act, he would neglect or refuse to execute the law. What would be the sworn duty of the President? Could he say that the Constitution did not bind him to see the law faithfully executed because it was one of his Secretaries and not himself upon whom the service was specially imposed? Might he not be asked whether there was any such limitation to his obligations prescribed in the Constitution? Whether he is not equally bound to take care that the laws be faithfully executed, whether they impose duties on the highest officer of State or the lowest subordinate in any of the Departments? Might he not be told that it was for the sole purpose of causing all executive officers, from the highest to the lowest, faithfully to perform the services required of them by law that the people of the United States have made him their Chief Magistrate and the Constitution has clothed him with the entire executive power of this Government? The principles implied in these questions appear too plain to need elucidation.

But here also we have a contemporaneous construction of the act which shows that it was not understood as in any way changing the relations between the President and Secretary of the Treasury, or as placing the latter out of Executive control even in relation to the deposits of the public money. Nor on that point are we left to any equivocal testimony. The documents of the Treasury Department show that the Secretary of the Treasury did apply to the President and obtained his approbation and sanction to the original transfer of the public deposits to the present Bank of the United States, and did carry the measure into effect in obedience to his decision. They also show that transfers of the public deposits from the branches of the Bank of the United States to State banks at Chillicothe, Cincinnati, and Louisville, in 1819, were made with the approbation of the President and by his authority. They show that upon all important questions appertaining to his Department, whether they related to the public deposits or other matters, it was the constant practice of the Secretary of the Treasury to obtain for his acts the approval and sanction of the President. These acts and the principles on which they were rounded were known to all the departments of the Government, to Congress and the country, and until very recently appear never to have been called in question.

Thus was it settled by the Constitution, the laws, and the whole practice of the Government that the entire executive power is vested in the President of the United States; that as incident to that power the right of appointing and removing those officers who are to aid him in the execution of the laws, with such restrictions only as the Constitution prescribes, is vested in the President; that the Secretary of the Treasury is one of those officers; that the custody of the public property and money is an Executive function which, in relation to the money, has always been exercised through the Secretary of the Treasury and his subordinates; that in the performance of these duties he is subject to the supervision and control of the President, and in all important measures having relation to them consults the Chief Magistrate and obtains his approval and sanction; that the law establishing the bank did not, as it could not, change the relation between the President and the Secretary--did not release the former from his obligation to see the law faithfully executed nor the latter from the President's supervision and control; that afterwards and before the Secretary did in fact consult and obtain the sanction of the President to transfers and removals of the public deposits, and that all departments of the Government, and the nation itself, approved or acquiesced in these acts and principles as in strict conformity with our Constitution and laws.

During the last year the approaching termination, according to the provisions of its charter and the solemn decision of the American people, of the Bank of the United States made it expedient, and its exposed abuses and corruptions made it, in my opinion, the duty of the Secretary of the Treasury, to place the moneys cf the United States in other depositories. The Secretary did not concur in that opinion, and declined giving the necessary order and direction. So glaring were the abuses and corruptions of the bank, so evident its fixed purpose to persevere in them, and so palpable its design by its money and power to control the Government and change its character, that I deemed it the imperative duty of the Executive authority, by the exertion of every power confided to it by the Constitution and laws, to check its career and lessen its ability to do mischief, even in the painful alternative of dismissing the head of one of the Departments. At the time the removal was made other causes sufficient to justify it existed, but if they had not the Secretary would have been dismissed for this cause only.

His place I supplied by one whose opinions were well known to me, and whose frank expression of them in another situation and generous sacrifices of interest and feeling when unexpectedly called to the station he now occupies ought forever to have shielded his motives from suspicion and his character from reproach. In accordance with the views long before expressed by him he proceeded, with my sanction, to make arrangements for depositing the moneys of the United States in other safe institutions.

The resolution of the Senate as originally framed and as passed, if it refers to these acts, presupposes a right in that body to interfere with this exercise of Executive power. If the principle be once admitted, it is not difficult to perceive where it may end. If by a mere denunciation like this resolution the President should ever be induced to act in a matter of official duty contrary to the honest convictions of his own mind in compliance with the wishes of the Senate, the constitutional independence of the executive department would be as effectually destroyed and its power as effectually transferred to the Senate as if that end had been accomplished by an amendment of the Constitution. But if the Senate have a right to interfere with the Executive powers, they have also the right to make that interference effective, and if the assertion of the power implied in the resolution be silently acquiesced in we may reasonably apprehend that it will be followed at some future day by an attempt at actual enforcement. The Senate may refuse, except on the condition that he will surrender his opinions to theirs and obey their will, to perform their own constitutional functions, to pass the necessary laws, to sanction appropriations proposed by the House of Representatives, and to confirm proper nominations made by the President. It has already been maintained (and it is not conceivable that the resolution of the Senate can be based on any other principle) that the Secretary of the Treasury is the officer of Congress and independent of the President; that the President has no right to control him, and consequently none to remove him. With the same propriety and on similar grounds may the Secretary of State, the Secretaries of War and the Navy, and the Postmaster-General each in succession be declared independent of the President, the subordinates of Congress, and removable only with the concurrence of the Senate. Followed to its consequences, this principle will be found effectually to destroy one coordinate department of the Government, to concentrate in the hands of the Senate the whole executive power, and to leave the President as powerless as he would be useless--the shadow of authority after the substance had departed.

The time and the occasion which have called forth the resolution of the Senate seem to impose upon me an additional obligation not to pass it over in silence. Nearly forty-five years had the President exercised, without a question as to his rightful authority, those powers for the recent assumption of which he is now denounced. The vicissitudes of peace and war had attended our Government; violent parties, watchful to take advantage of any seeming usurpation on the part of the Executive, had distracted our councils; frequent removals, or forced resignations in every sense tantamount to removals, had been made of the Secretary and other officers of the Treasury, and yet in no one instance is it known that any man, whether patriot or partisan, had raised his voice against it as a violation of the Constitution. The expediency and justice of such changes in reference to public officers of all grades have frequently been the topic of discussion, but the constitutional right of the President to appoint, control, and remove the head of the Treasury as well as all other Departments seems to have been universally conceded. And what is the occasion upon which other principles have been first officially asserted? The Bank of the United States, a great moneyed monopoly, had attempted to obtain a renewal of its charter by controlling the elections of the people and the action of the Government. The use of its corporate funds and power in that attempt was fully disclosed, and it was made known to the President that the corporation was putting in train the same course of measures, with the view of making another vigorous effort, through an interference in the elections of the people, to control public opinion and force the Government to yield to its demands. This, with its corruption of the press, its violation of its charter, its exclusion of the Government directors from its proceedings, its neglect of duty and arrogant pretensions, made it, in the opinion of the President, incompatible with the public interest and the safety of our institutions that it should be longer employed as the fiscal agent of the Treasury. A Secretary of the Treasury appointed in the recess of the Senate, who had not been confirmed by that body, and whom the President might or might not at his pleasure nominate to them, refused to do what his superior in the executive department considered the most imperative of his duties, and became in fact, however innocent his motives, the protector of the bank. And on this occasion it is discovered for the first time that those who framed the Constitution misunderstood it; that the First Congress and all its successors have been under a delusion; that the practice of near forty-five years is but a continued usurpation; that the Secretary of the Treasury is not responsible to the President, and that to remove him is a violation of the Constitution and laws for which the President deserves to stand forever dishonored on the journals of the Senate.

There are also some other circumstances connected with the discussion and passage of the resolution to which I feel it to be not only my right, but my duty, to refer. It appears by the Journal of the Senate that among the twenty-six Senators who voted for the resolution on its final passage, and who had supported it in debate in its original form, were one of the Senators from the State of Maine, the two Senators from New Jersey, and one of the Senators from Ohio. It also appears by the same Journal and by the files of the Senate that the legislatures of these States had severally expressed their opinions in respect to the Executive proceedings drawn in question before the Senate.

The two branches of the legislature of the State of Maine on the 25th of January, 1834, passed a preamble and series of resolutions in the following words:

Whereas at an early period after the election of Andrew Jackson to the Presidency, in accordance with the sentiments which he had uniformly expressed, the attention of Congress was called to the constitutionality and expediency of the renewal of the charter of the United States Bank; and

Whereas the bank has transcended its chartered limits in the management of its business transactions, and has abandoned the object of its creation by engaging in political controversies, by wielding its power and influence to embarrass the Administration of the General Government, and by bringing insolvency and distress upon the commercial community; and

Whereas the public security from such an institution consists less in its present pecuniary capacity to discharge its liabilities than in the fidelity with which the trusts reposed in it have been executed; and

Whereas the abuse and misapplication of the powers conferred have destroyed the confidence of the public in the officers of the bank and demonstrated that such powers endanger the stability of republican institutions: Therefore,

Resolved , That in the removal of the public deposits from the Bank of the United States, as well as in the manner of their removal, we recognize in the Administration an adherence to constitutional rights and the performance of a public duty.

Resolved , That this legislature entertain the same opinion as heretofore expressed by preceding legislatures of this State, that the Bank of the United States ought not to be rechartered.

Resolved, That the Senators of this State in the Congress of the United States be instructed and the Representatives be requested to oppose the restoration of the deposits and the renewal of the charter of the United States Bank.

On the 11th of January, 1834 the house of assembly and council composing the legislature of the State of New Jersey passed a preamble and a series of resolutions in the following words:

Whereas the present crisis in our public affairs calls for a decided expression of the voice of the people of this State; and

Whereas we consider it the undoubted right of the legislatures of the several States to instruct those who represent their interests in the councils of the nation in all matters which intimately concern the public weal and may affect the happiness or well-being of the people: Therefore,

1. Be it resolved by the council and general assembly of this State , That while we acknowledge with feelings of devout gratitude our obligations to the Great Ruler of Nations for His mercies to us as a people that we have been preserved alike from foreign war, from the evils of internal commotions, and the machinations of designing and ambitious men who would prostrate the fair fabric of our Union, that we ought nevertheless to humble ourselves in His presence and implore His aid for the perpetuation of our republican institutions and for a continuance of that unexampled prosperity which our country has hitherto enjoyed.

2. Resolved, That we have undiminished confidence in the integrity and firmness of the venerable patriot who now holds the distinguished post of Chief Magistrate of this nation, and whose purity of purpose and elevated motives have so often received the unqualified approbation of a large majority of his fellow-citizens.

3. Resolved, That we view with agitation and alarm the existence of a great moneyed incorporation which threatens to embarrass the operations of the Government and by means of its unbounded influence upon the currency of the country to scatter distress and ruin throughout the community, and that we therefore solemnly believe the present Bank of the United States ought not to be rechartered.

4. Resolved, That our Senators in Congress be instructed and our members of the House of Representatives, be requested to sustain, by their votes and influence, the course adopted by the Secretary of the treasury, Mr. Taney, in relation to the Bank of the United States and the deposits of the Government moneys, believing as we do the course of the Secretary to have been constitutional, and that the public good required its adoption.

5. Resolved, That the governor be requested to forward a copy of the above resolutions to each of our Senators and Representatives from this State to the Congress of the United States.

On the 21st day of February last the legislature of the same State reiterated the opinions and instructions before given by joint resolutions in the following words:

Resolved by the council and general assembly of the State of New Jersey, That they do adhere to the resolutions passed by them on the 11th day of January last, relative to the President of the United States, the Bank of the United States, and the course of Mr. Taney in removing the Government deposits.

Resolved , That the legislature of New Jersey have not seen any reason to depart from such resolutions since the passage thereof, and it is their wish that they should receive from our Senators and Representatives of this State in the Congress of the United States that attention and obedience which are due to the opinion of a sovereign State openly expressed in its legislative capacity.

On the 2d of January, 1834, the senate and house of representatives composing the legislature of Ohio passed a preamble and resolutions in the following words:

Whereas there is reason to believe that the Bank of the United States will attempt to obtain a renewal of its charter at the present session of Congress; and

Whereas it is abundantly evident that said bank has exercised powers derogatory to the spirit of our free institutions and dangerous to the liberties of these United States; and

Whereas there is just reason to doubt the constitutional power of Congress to grant acts of incorporation for banking purposes out of the District of Columbia; and

Whereas we believe the proper disposal of the public lands to be of the utmost importance to the people of these United States, and that honor and good faith require their equitable distribution: Therefore,

Resolved by the general assembly of the State of Ohio, That we consider the removal of the public deposits from the Bank of the United States as required by the best interests of our country, and that a proper sense of public duty imperiously demanded that that institution should be no longer used as a depository of the public funds.

Resolved also , That we view with decided disapprobation the renewed attempts in Congress to secure the passage of the bill providing for the disposal of the public domain upon the principles proposed by Mr. Clay, inasmuch as we believe that such a law would be unequal in its operations and unjust in its results.

Resolved also, That we heartily approve of the principles set forth in the late veto message upon that subject; and

Resolved , That our Senators in Congress be instructed and our Representatives requested to use their influence to prevent the rechartering of the Bank of the United States, to sustain the Administration in its removal of the public deposits, and to oppose the passage of a land bill containing the principles adopted in the act upon that subject passed at the last session of Congress.

Resolved , That the governor be requested to transmit copies of the foregoing preamble and resolutions to each of our Senators and Representatives.

It is thus seen that four Senators have declared by their votes that the President, in the late Executive proceedings in relation to the revenue, had been guilty of the impeachable offense of "assuming upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws, but in derogation of both," whilst the legislatures of their respective States had deliberately approved those very proceedings as consistent with the Constitution and demanded by the public good. If these four votes had been given in accordance with the sentiments of the legislatures, as above expressed, there would have been but twenty-two votes out of forty-six for censuring the President, and the unprecedented record of his conviction could not have been placed upon the Journal of the Senate.

In thus referring to the resolutions and instructions of the State Legislatures, I disclaim and repudiate all authority or design to interfere with the responsibility due from members of the Senate to their own consciences, their constituents and their country. The facts now stated belong to the history of these proceedings, and are important to the just development of the principles and interests involved in them, as well as to the proper vindication of the Executive Department; and with that view, and that view only, are they here made the topic of remark.

The dangerous tendency of the doctrine which denies to the President the power of the supervising, directing, and removing the Secretary of the Treasury, in like manner with other Executive offices, would soon be manifest in practice, were the doctrine to be established. The President is the direct representative of the American People, but the Secretaries are not. If the Secretary of the Treasury be independent of the President in the execution of the laws, then is there no direct responsibility to the People in the important branch of this Government, to which is committed the care of the national finances. And it is in the power of the Bank of the United States, or any other corporation, body of men, or individuals, if a Secretary, shall be found to accord with them in opinion, or can be induced in practice to promote their views, to control, through him, the whole action of Government, (so far as it is exercised by his Department,) in defiance of the Chief Magistrate elected by the People and responsible to them.

But the evil tendency of the particular doctrine adverted to, though superficially serious, would be as nothing in comparison with the pernicious consequences which would inevitably flow from the approbation and allowance by the People, and the practice by the Senate, of the unconstitutional power of arraigning and censuring the official conduct of the Executive, in the manner recently pursued. Such proceedings are eminently calculated to unsettle the foundations of the Government; to disturb the harmonious action of the different Departments: and to break down the checks and balances by which the wisdom of its framers sought to ensure its stability and usefulness.

The honest differences of opinion which occasionally exist between the Senate and President, in regard to matters in which both are obliged to participate, are sufficiently embarrassing. But if the course recently adopted by the Senate shall hereafter be frequently pursued, it is not only obvious that the harmony of the relations between the President and the Senate will be destroyed, but that other and graver effects will ultimately ensue. If the censures of the Senate be submitted to by the President, the confidence of the People in his ability and virtue and the character and usefulness of his administration, will soon be at an end, and the real power of the Government will fall into the hands of a body, holding their offices for long terms, not elected by the People, and not to them directly responsible. If, on the other hand, the illegal censures of the Senate should be resisted by the President, collisions and angry controversies might ensue, discreditable in their progress, and in the end compelling the People to adopt the conclusion, either that their Chief Magistrate was unworthy of their respect, or that the Senate was chargeable with calumny and injustice. Either of these results would impair public confidence in the perfection of the system, and lead to serious alterations of its frame work, or to the practical abandonment of some of its provisions.

The influence of such proceedings in the other departments of the Government, and more especially on the States, could not fail to be extensively pernicious. When the judges in the last resort of official misconduct, themselves overleaped the bounds of their authority, as prescribed by the Constitution, what general disregard of its provisions might not their example be expected to produce? And who does not perceive that such contempt of the Federal Constitution, by one of its most important Departments, would hold out the strongest temptation to resistance on the part of the State sovereignties, whenever they shall suppose their just rights to have been invaded? Thus all the independent Departments of the Government, and the States which compose our confederated Union, instead of attending to their appropriate duties, and leaving those who may offend, to be reclaimed or punished in the manner pointed out in the Constitution, would fall to mutual crimination and recrimination, and give to the People, confusion and anarchy, instead of order and law; until at length some form of aristocratic power would be established on the ruins of the Constitution, or the States be broken into separate communities.

Far be it from me to charge, or to insinuate, that the present Senate of the United States intended in the most distant way, to encourage such a result. It is not of their motives or designs but only of the tendency of their acts, that is my duty to speak. It is, if possible, to make Senators themselves sensible of the danger which lurks under the precedent set in their resolution; and at any rate to perform my duty, as the responsible Head of one of the co-equal Departments of the Government, that I have been compelled to point out the consequences to which the discussion and passage of the resolutions may lead, if the tendency of the measure be not checked in its inception. It is due to the high trust with which I have been charged; to those who may be called to succeed me in it; to the Representatives of the People, whose constitutional prerogative has been unlawfully assumed; to the People and to the States; and to the Constitution they have established; that I shall not permit its provisions to be broken down by such an attack on the Executive Department, without at least some effort " to preserve, protect, and defend them."

With this view, and for the reasons which have been stated, I do hereby solemnly protest against the aforementioned proceedings of the Senate, as unauthorized by the Constitution; contrary to its spirit and to several of its express provisions; subversive of that distribution of the powers of government which it has ordained and established; destructive of the checks and safe guards by which those powers were intended, on the one hand to be controlled, and on the other to be protected and calculated by their immediate and collateral effects, by their character and tendency, to concentrate in the hands of a body not directly amenable to the People, a degree of influence and power dangerous to their liberties, and fatal to the Constitution of their choice.

The resolution of the Senate contains an imputation upon my private as well as upon my public character; and as it must stand forever on their journals, I cannot close this substitute for that defense which I have not been allowed to present in the ordinary form, without remarking, that I have lived in vain, if it be necessary to enter into a formal vindication of my character and purpose from such an imputation. In vain do I bear upon my person, enduring memorials of that contest in which American liberty was purchased—in vain have I since periled property, fame, and life, in defense of the rights and privileges so dearly bought—in vain am I now, without a personal aspiration, or the hope of individual advantage, encountering responsibilities and dangers, from which, by mere inactivity in relation to a single point, I might have been exempt—if any serious doubts can be entertained as to the purity of my purpose and motives. If I had been ambitious, I should have sought an alliance with that powerful institution, which even now aspires to no divided empire. If I had been venal, I should have sold myself to its designs—had I preferred personal comfort and official ease to the performance of my arduous duty, I should cease to molest it. In the history of conquerors and usurpers, never, in the fire of youth, nor in the vigor of manhood, could I find an attraction to lure me from the path of duty; and now, I shall scarcely find an inducement to commence their career of ambition, when gray' hairs and a decaying frame, instead of inviting to toil and battle, call me' to the contemplation of other worlds, where conquerors cease to be honored, and usurpers expiate their crimes. The only ambition I can feel, is to acquit myself to Him to whom I must soon render an account of my stewardship, to serve my fellow men, and live respected and honored in the history of my country. No; the ambition which leads me on, is an anxious desire and a fixed determination, to return to the people unimpaired, the sacred trust they have confided to my charge—to heal the wounds of the Constitution and preserve it from further violation; to persuade my countrymen, so far as I may, that it is not in a splendid Government, supported by powerful monopolies and aristocratical establishments, that they will find happiness, or their liberties protection ; but in a plain system, void of pomp—protecting all, and granting favors to none—dispensing its blessings like the dews of Heaven, unseen and unfelt, save in the freshness and beauty they contribute to produce. It is such a Government that the genius of our people requires—such a one only under which our States may remain for ages to come, united, prosperous, and free. If the Almighty Being who has hitherto sustained and protected me, will but vouchsafe to make my feeble powers instrumental to such a result, I shall anticipate with pleasure the place to be assigned me in the history of my country, and die contented with the belief, that I have contributed, in some small degree, to increase the value and prolong the duration of American Liberty.

To the end that the resolution of the Senate may not be hereafter drawn into precedent, with the authority of silent acquiescence on the part of the executive department, and to the end, also, that my motives and views in the Executive proceedings denounced in that resolution, may be known to my fellow-citizens, to the world and to all posterity, I respectfully request that this Message and Protest may be entered at length on the Journal of the Senate.

*The Senate ordered that it be not entered on the Journal.

[APP Note: This message was incorrectly listed as a "veto message" by James Richardson in "The Messages and Papers of the Presidents." The American Presidency Project was notified of this error by Prof. Fred I. Greenstein and it has been re-titled and categorized as a "Message to Congress" rather than a "veto message."]

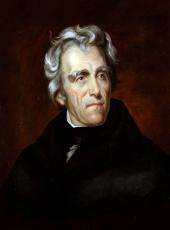

Andrew Jackson, Message to the Senate Protesting Censure Resolution (*) Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/201670