Thank you. The United States of America, history's most successful political experiment, has proved that a nation conceived in liberty will prove stronger, more decent and enduring than any nation ordered to exalt the few at the expense of the many or made from a common race or culture or to preserve traditions that have no greater attribute than longevity. Our war with radical Islamic extremists has been wrongly described as a clash of civilizations. It is a clash of ideals, not civilizations, a profound and hugely consequential clash of ideals. It is a fight between right and wrong, in which relativism should have no place. We are defending our security and ideals from an attack by those who consider liberty immoral. We're not defending an idea that every human being should eat corn flakes, play baseball or watch MTV. We're not insisting that all societies be governed by a bicameral legislature and a term-limited chief executive. We are insisting that all people have a God-given right to be free, and that right is not subject to the whims and interests and authority of another person, government or culture. And central to our ideals is the sanctity of property rights. Without private property there can be no freedom, and without freedom there can be no America.

Property," John Adams wrote, "is surely a right of mankind as real as liberty." Yet today property rights come under attack from regulations that affect every conceivable aspect of property ownership. Mr. Adams would be shocked to learn what both the United States Supreme Court and the Supreme Court of Connecticut did to Susette Kelo, an American homeowner, in allowing the government to seize her home for economic development and gain under the guise of "valid public use."

The protection of property rights lies at the heart of our constitutional system. The Framers of our Constitution drew upon classical notions of legal rights and individual liberty dating back to the Justinian Code, the Magna Carta, and the Two Treatises of John Locke, all of which recognize the importance of property ownership in a governmental system in which individual liberty and the free market are paramount.

Property is more than just land. Property is buildings, machines, apartment leases, retirement savings accounts, checking accounts, furniture, computers, cars, and even ideas. In short, property is the fruit of one's labor. Property rights protection means that the individual reaps the rewards from the sweat of his brow, not the government or those who control the government. Our economy is built on the labors of American workers and fueled by the dreams of innovators and entrepreneurs. Without secure private property, the incentives that have made America the greatest exporter, importer, producer, saver, investor, manufacturer, and innovator on the globe would whither.

This insight has produced a revolution in development strategies around the globe. After decades of literally throwing money at the problem of global poverty, the emphasis has switched to securing property rights, buttressing the rule of law and allowing the world's workers to profit from their labor and retain its rewards.

Indeed, where the fruits of one's labors are owned by the State and not the individual, people are powerless. As Noah Webster explained: "Let the people have property and they will have power a power that will forever be exerted to prevent the restriction of the press, the abolition of trial by jury, or the abridgment of many other privileges." In sharp contrast, Karl Marx wrote in the Communist Manifesto: "The theory of the Communists may be summed up in a single sentence: Abolition of private property."

The Government's disrespect for property rights, in the form of taxation without representation and the seizing of private homes for troops without permission or compensation, was the motivating force behind our struggle to obtain independence. And in the years after achieving independence, the Founders ensured that the property rights for which they fought were protected by our Constitution. They recognized that liberty and property rights are inseparable. As James Madison stated, "It is sufficiently obvious, that persons and property are the two great subjects on which Governments are to act; and that the rights of persons, and the rights of property, are the objects, for the protection of which Government was instituted."

One of the most visible protections for property rights is the Just Compensation Clause of the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution, which states: "nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation." The purpose of the Just Compensation Clause, as interpreted by the Supreme Court in Armstrong v. United States, is "to bar Government from forcing some people to bear public burdens, which in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole."

Some local governments have sought to stretch their eminent domain power as a means of augmenting revenue by expanding their tax base. Indeed, the America of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries has witnessed an explosion of government regulations that have jeopardized private ownership of property, often for questionable purposes that have little to do with the limited types of public use envisioned by the framers of our Constitution.

The need to protect private property rights, once so obvious to Madison and Adams is now becoming lost in a tangle of intrusive government takings. Nowhere has this been truer than in the disastrous decision issued in 2005 by the U.S. Supreme Court in Kelo v. City of New London.

In Kelo, the Supreme Court held that held that the Constitution allows governments to seize private property and transfer it from one private land owner to another in the name of economic development. In other words, after the Kelo decision, governments can use their eminent domain power to take homes for potentially more profitable, higher-tax uses, powerful evidence, as Justice Clarence Thomas suggests, that something is seriously awry with the Supreme Court's vision of the Constitution. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor framed the problem very simply in her blistering dissenting opinion: "Under the banner of economic development, all private property is now vulnerable to being taken and transferred to another private owner, so long as it might be upgraded i.e., given to an owner who will use it in a way that the legislature deems more beneficial to the public in the process." This decision went well beyond what the founders intended when they wrote the just compensation for public use clause.

Justice O'Connor foresaw that that "the beneficiaries of Kelo are likely to be those citizens with disproportionate influence and power in the political process, including large corporations and development firms. As for the victims, the government now has license to transfer property from those with fewer resources to those with more."

The Kelo decision gives any government entity the ability to take a person's property and give it to a developer. It represents one of the most alarming reductions of freedom in our lifetimes. An editorial from the Telegraph Herald in Dubuque put it best: "If creating new tax revenue is considered an applicable public use, homeowners' rights become vastly unstable. Almost any development could create greater tax revenue than a single home or two." Your home, as the saying goes, is your castle; it is not supposed to be the site of a new shopping mall unless you say so. And Susette Kelo did not say so. And by ignoring her right to do so, by reducing her freedom, the Court also revealed an astonishing lack of respect for the efficiency and fairness of free markets.

Des Moines Register columnist David Yepsen argued: "Instead of forcing people to sell property to governments at mediocre rates, developers will have to a pay a high enough price so that the property owner becomes a willing seller." And if they still don't want to sell, well, that's their choice. Yet, within one year after this disastrous decision, reports have surfaced that nearly 6,000 properties nationwide were threatened or taken as a result of this decision, representing a dramatic upward spike in the number of takings.

And it is not just homeowners who face this threat. It is a threat shared by millions of small business owners across the country. Following Kelo, the millions of people who have struggled to grow their small businesses may find themselves forced to sell if the local government decides that their property could be put to better use by a bigger business or larger competitor.

In state after state, polls make clear that the American public understands the Kelo ruling is a disaster: 82 percent of Ohioans oppose using eminent domain to take property for economic development, 91 percent of Minnesotans, 92 percent of Kansans, 95 percent of Coloradans, and 86 percent of Missourians. The American public has spoken with one voice, and they're saying that this is not right.

I have co-sponsored legislation to forbid this kind of government taking; Congress and the States should follow Iowa's lead and pass such laws. But laws defending private property are only as secure as the judges that defend those laws. Kelo passed narrowly, supported by a five to four majority with a track record of legislating from the bench. As President, I pledge to appoint strict constructionist judges who respect the Constitution and understand the security of private property it provides. If need be, I would seek to amend the Constitution to protect private property rights in America.

Those of us privileged to lead this country need only be mindful of what has always made us great, have the courage to stand by our principles, honor our public trust, and keep our promises to put the country's interests before our own.

I've always kept my promises to my country. I'll keep the ones I make now. And I will keep the ones I make as President. Thank you.

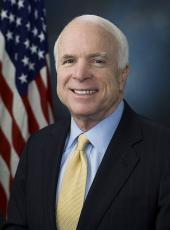

John McCain, Address to the Cedar Rapids Rotary Club Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/277323