Address to the 108th National Convention Of The Veterans Of Foreign Wars in Kansas City, Missouri

Thank you very much for that warm welcome, and for inviting me to address you. This is not the first time I have had the honor of speaking at your convention. I'm always grateful for the opportunity, and pleased to be in the company of Americans who have had the burden of serving our country in distant lands, and the honor of having proved your patriotism in difficult circumstances.

I was blessed to have been born into a family who made their living at sea in defense of our security and ideals. My grandfather was a naval aviator; my father a submariner. Their respect for me was one of the great ambitions of my life. And so it was nearly pre-ordained that I would find a place in my family's profession, and that occupation would one day take me to war.

Such was not the case for many of you. Your ambitions might not have led you to war; the honors you sought were not kept hidden on battlefields. Many of you were citizen-soldiers. You answered the call when it came; took up arms for your country's sake; and fought to the limit of your ability because you believed America's security was as much your responsibility as it was the professional soldier's. And when you came home, you built a better a country than the one you inherited.

I did what I had prepared much of my life to do. You did what I did and more but without the advantages of training and experience that I possessed. Many of you were kids when you saw combat. I was thirty years old. I believe you outrank me.

I do not mean to dismiss the virtues of the professional soldier. I consider my inclusion in their ranks to be one of the great honors of my life. The Navy was and still remains the world I know best and love most. The Navy took me to war.

Unless you are a veteran you might find it odd that I would be indebted to the Navy for sending me to war. You might conclude mistakenly that the secret bond veterans share is that we enjoyed war. But as most veterans know, war is an experience we would not trade and we would rather not repeat.

We do share a secret, but it is not a romantic remembrance of war. War is awful. When nations seek to resolve their differences by force of arms, a million tragedies ensue. Nothing, not the valor with which it is fought nor the nobility of the cause it serves, can glorify war. War is wretched beyond all description. Whatever gains are secured, it is loss the veteran remembers most keenly. Only a fool or a fraud sentimentalizes the cruel and merciless reality of war.

Neither do we share nostalgia for the exhilaration of combat. That exhilaration, after all, is really the sensation of choking back fear. We might be proud to have overcome the paralysis of terror. But few of us are so removed from the experience to mistake it today for a welcome thrill.

What we share is something harder to explain. It is in part appreciation for having sacrificed for a cause greater than ourselves; relief for having your courage and honor tested and affirmed in the fearsome crucible of combat; pride for having replaced comfort and security with misery and deprivation and not been broken by the experience. But the most important thing we share, the bond that it is ours alone is very difficult for others who have not shared our experience to understand.

If you will excuse a few moments of shameless self promotion, I want to quote from a passage I wrote in a book published last week, entitled, Hard Call, which examines a number of historically important decisions and how and why they were made. It's available in better bookstores everywhere and at Amazon.com for $25.99, a bargain at twice the price. Commercial opportunity aside, I reference the book because in several chapters I tried to explain briefly my thoughts about war; its nature and paradoxes; the mistakes that are often made; the attributes of successful commanders, the experience of fighting, and the unique purpose that is the combat veteran's. It is the last subject that interested me as I tried to describe the relationship between Robert Gould Shaw, who you might remember was the white commanding officer of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in the Civil War, and the African American volunteers he had the honor to co mmand.

In the end, all soldiers fight for the same cause. Some defend the right and some the wrong. Some embrace the cause their nation summoned them to fight. Some perceive other interests of the state in their summons, less noble or selfless perhaps, but serve out of a sense of patriotic duty. Some fight because they are professional soldiers and proud to do the job they have been trained to do. Some fight to prove themselves or to avenge an injury to their country's honor or their own. Some fight because they would be ashamed not to or to make something of themselves in the exhilarating challenge and spectacle of combat. Some fight to make the world better and some to keep the world from threatening their little piece of it. Some fight eagerly and some reluctantly.

But in the upheaval of war, that great leveler of ego and distinction, things change. War is a remorseless scavenger, hacking through the jungle of deceit, pretense, and self-delusion to find truth, some of it ugly, some of it starkly beautiful; to find virtue and expose iniquity where we never expected them to reside. No other human experience exists on the same plane. It is a surpassing irony that war, for all the horrors and heroism it occasions, provides the soldier with every conceivable human experience. Experiences that usually take a lifetime to know are all felt, and felt intensely, in one brief passage of life. Anyone who loses a loved one knows what great sorrow feels like. And anyone who gives life to a child knows what great joy feels like. The combat veteran knows what great loss and great joy feel like when they occur in the same moment, the same experience. It can be transforming.

However glorious the cause liberty, union, conquering tyranny it does not define the experience of war. War mocks our idealized conceptions of glory, whether they are genuine and worthy or something less. War has its own truths. And if glory can be found in war, it is a different concept altogether. It is a hard-pressed, bloody, and soiled glory, steely and forbearing. It is the decency and love persisting amid awful degradation, in unsurpassed suffering, misery and cruelty. It is the discovery that we belong to something bigger than ourselves, that our individual identity tested, injured, and changed by war is not our only cherished possession. That something is not an ideal but a community, a fraternity of arms. Soldiers are responsible for defending the cause for which their war is fought and for which they will lay down their lives. But it is their war, and they have their own causes.

In the immediacy, chaos, destruction, and shock of war, soldiers are bound by duty and military discipline to endure and overcome. Their strongest loyalty, the bond that cannot break, is to the cause that is theirs alone, the cause for which they all fight: one another. It is through loyalty to comrades in arms, their exclusive privilege, that they serve the national ideal that begat their personal transformation. When war is over, they might have the largest but not exclusive claim on the success of their nation's cause. But their claim is shorn of all romance, all nostalgia for the crucible in which it was won. From that crucible they have but one prize, one honor, one glory: that they had withstood the savagery and losses of war and were found worthy by the men who stood with them."

That is a distinction no other Americans can claim, and it came at a great price. The sacrifices made by veterans deserve to be memorialized in something more lasting than marble or bronze or in the fleeting effect of a politician's speeches. Your valor and devotion to duty have earned your country's abiding concern for your welfare. And when our government forgets to honor the country's debts to you, it is a stain upon America's honor. The Walter Reed scandal recalled, I hope, not just government but the public who elected it, to our responsibilities to the men and women who risked life and limb to meet their responsibilities to us. Such a disgrace is unworthy of the greatest nation on earth. As the greatest leaders in our history, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, instructed us, care for Americans who fought to defend us should rank among the highest of national priorities.

The world in which many of us served was a dangerous one, but more stable than the world today. It was a world where we confronted a massive, organized threat to our security. Our enemy was evil, but not irrational. And for all the suffering endured by captive nations; for all the fear of global nuclear war; it was a world made fairly predictable by a stable balance of power until our steadfastness and patience yielded an historic victory for our security and ideals. That world is gone, and please don't mistake my reminiscence as an indication that I miss it. If I'm nostalgic for it at all, it is only an old man's nostalgia for the time where he misspent his youth. That world, after all, had much cruelty and terror, some of which it was our fate to witness personally.

Today, we glimpse the prospect of another, better world, in which all people might someday share in the blessings and responsibilities of freedom. But we also face a threat, and a long war to defeat it, that is as difficult and in many respects more destabilizing than any challenge we have ever faced. We confront an enemy that so despises us and modernity itself that they would use any means, unleash any terror, cause the most unimaginable suffering to harm us, and to destroy the world we have tried throughout our history to build.

As we meet, in Iraq and Afghanistan, American soldiers, Marines, sailors and airmen are fighting bravely and tenaciously in battles that are as dangerous, difficult and consequential as the great battles of our armed forces' storied past. As we all know, the war in Iraq has not gone well, and the American people have grown sick and tired of it. I understand that, of course. I, too, have been made sick at heart by the many mistakes made by civilian and military commanders and the terrible price we have paid for them. But we cannot react to these mistakes by embracing a course of action that will be an even greater mistake, a mistake of colossal historical proportions, which will and I am as sure of this as I am of anything seriously endanger the country I have served all my adult life.

We have new commanders in Iraq, and they are following a counterinsurgency strategy that we should have been following from the beginning, which makes the most effective use of our strength and doesn't strengthen the tactics of our enemy. This new battle plan is succeeding where our previous tactics failed. Although the outcome remains uncertain, we must give General Petraeus and the Americans he has the honor to command adequate time to salvage from the wreckage of our past mistakes a measure of stability for Iraq and the Middle East, and a more secure future for the American people. To concede defeat now would strengthen al Qaeda, empower Iran and other hostile powers in the Middle East, unleash a full scale civil war in Iraq that could quite possibly provoke genocide there, and destabilize the entire region as neighboring powers come to the aid of their favored factions. The consequences would threaten us for years, and I am certain would eventua lly draw us into a wider and more difficult war that would impose even greater sacrifices on us.

Our defeat in Iraq would be catastrophic, not just for Iraq, but for us, and I cannot be complicit in it. I will do whatever I can, whether I am effective or not, to help avert it. That is all I can offer my country. It is not much compared to the sacrifices made by Americans who have volunteered to shoulder a rifle and fight this war for us. I know that and am humbled by it. But though my duty is neither dangerous nor onerous, it compels me nonetheless to say to my fellow Americans, as long as we have a chance to succeed we must try to succeed.

I have many responsibilities to the American people, and I try to take them all seriously. But I have one responsibility that outweighs all the others and that is to use whatever meager talents I possess, and every resource God has granted me to protect the security of this great and good nation from all enemies foreign and domestic. And that I intend to do, even if I must stand athwart popular opinion. I will attempt to convince as many of my countrymen as I can that we must show even greater patience, though our patience is nearly exhausted, and that as long as there is a prospect for not losing this war then we must not choose to lose it. That is how I construe my responsibility to my country. That is how I construed it yesterday. It is how I construe it today. It is how I will construe it tomorrow. I do not know how I could choose any other course.

War is a terrible thing, but not the worst thing. You know that, you have endured the dangers and deprivations of war so that the worst thing would not befall us, so that America might be secure in her freedom. The war in Iraq has divided the American people, but it has divided no American in our admiration for the men and women who are fighting for us there. It is every veteran's hope that should their children be called upon to answer a call to arms, the battle will be necessary and the field well chosen. But that is not their responsibility. It belongs to the government that called them. As it once was for us, their honor will be in their answer not their summons. Whatever we think about how and why we went to war in Iraq, we are all those who supported the decision that placed them in harm's way and those who opposed it humbled by and grateful for their example. They now deserve the distinction of the best Americans, and we owe them a debt we can never fully repay. We can only offer the small tribute of our humility and our commitment to do all that we can do, in less trying and costly circumstances, to help keep this nation worthy of their sacrifice.

Many of them have served multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many have had their tours extended. Many have returned to combat sooner than they had been led to expect. It is a sad and hard thing to ask so much more of Americans who have already given more than their fair share to the defense of our country. Few of them and their families will have received the news about additional and longer deployments without aiming a few appropriate complaints in the general direction of people like me, who helped make the decision to send them there. And then they shouldered a rifle and risked everything everything to accomplish their mission, to protect another people's freedom and our own country from harm.

It is a privilege beyond measure to live in a country served by them. I have lived a long, eventful and blessed life. I have had the good fortune to know personally a great many brave and selfless patriots who sacrificed and shed blood to defend America. But I have known none braver or better than those who do so today. They are our inspiration, as I suspect all of you were once theirs. And I pray to a loving God that He bless and protect them.

Thank you.

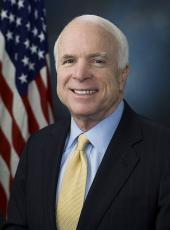

John McCain, Address to the 108th National Convention Of The Veterans Of Foreign Wars in Kansas City, Missouri Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/277016