What is the Meaning of Thanksgiving??

Here are three questions to pose while reading any Presidential Thanksgiving Proclamation:

- How often, and how explicitly, does the proclamation refer to God or a Supreme Being?

- What reference is made to customs in observing Thanksgiving, and do any of those references include mentions of American Indians?

- What reasons are given for giving thanks? For peace? For prosperity? For the families and friends we love?

Over time, there has been significant change in the ways Presidents answered these three questions. We explore that evolution in this analysis. (You can link to all of them through our "advanced search.")

Originally, Thanksgiving Proclamations were simply a call for a day of solemn reflection and expression of thanks to a Supreme Being. Over time, the Proclamations changed to add language claiming a distinctively American Thanksgiving history and to call for reinforcement of certain core values. (Jump to the list of proclamations)

Washington (in 1789 and 1795) and Madison (1815) proclaimed that there be a day of reflection and public thanksgiving for peace and abundance. Prior to that time and continuing afterward, days of thanksgiving had been observed in individual colonies and states. It was especially well-established as a family “domestic occasion” in New England. (Pleck, 775).

On What Day Do We Give Thanks?

Our current Thanksgiving practices begin with Lincoln’s second 1863 Thanksgiving proclamation (Proclamation 106). This provided for a Federal holiday tradition with a standardized date—the last Thursday in November. Until FDR, subsequent presidents followed Lincoln’s precedent as to timing.[1]

However, sometimes November includes five Thursdays. In those cases, the “last Thursday” is close in time to Christmas Day. Merchants learned that most Christmas shopping was delayed until after Thanksgiving. In response to concerns that a “late” Thanksgiving reduces consumer spending, Roosevelt, in 1939, proclaimed the observance to be on the fourth Thursday in November (November 23 vs. November 30 for the last Thursday).

Not all states followed Roosevelt’s change in the timing of the holiday, with nearly half observing the traditional “last Thursday,” thus creating "two Thanksgivings!" FDR’s controversial decision was codified and became nationally standardized is a resolution signed December 26, 1941 (H. J. Res 41) (55 Stat 862).

History and Reasons

In his precedent-setting 1863 proclamation, Lincoln noted that despite a terrible civil war, “laws have been respected and obeyed.” Especially remarkably, the nation’s economy and population had grown. These blessings “are the gracious gifts of the Most High God” who has shown mercy.

In recognition of these many good things, Lincoln called for a day of “thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens” as well as “humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience.” People should “fervently implore. . . the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it . . .”

The fundamental element in Lincoln’s model is the call for a day of gratitude for “the gracious gifts of the Most High God.” This idea, and also Lincoln's language, has been often echoed in subsequent Proclamations. In this view, an important, if not the only, purpose of Thanksgiving is to give thanks to a Supreme Being for all good things.

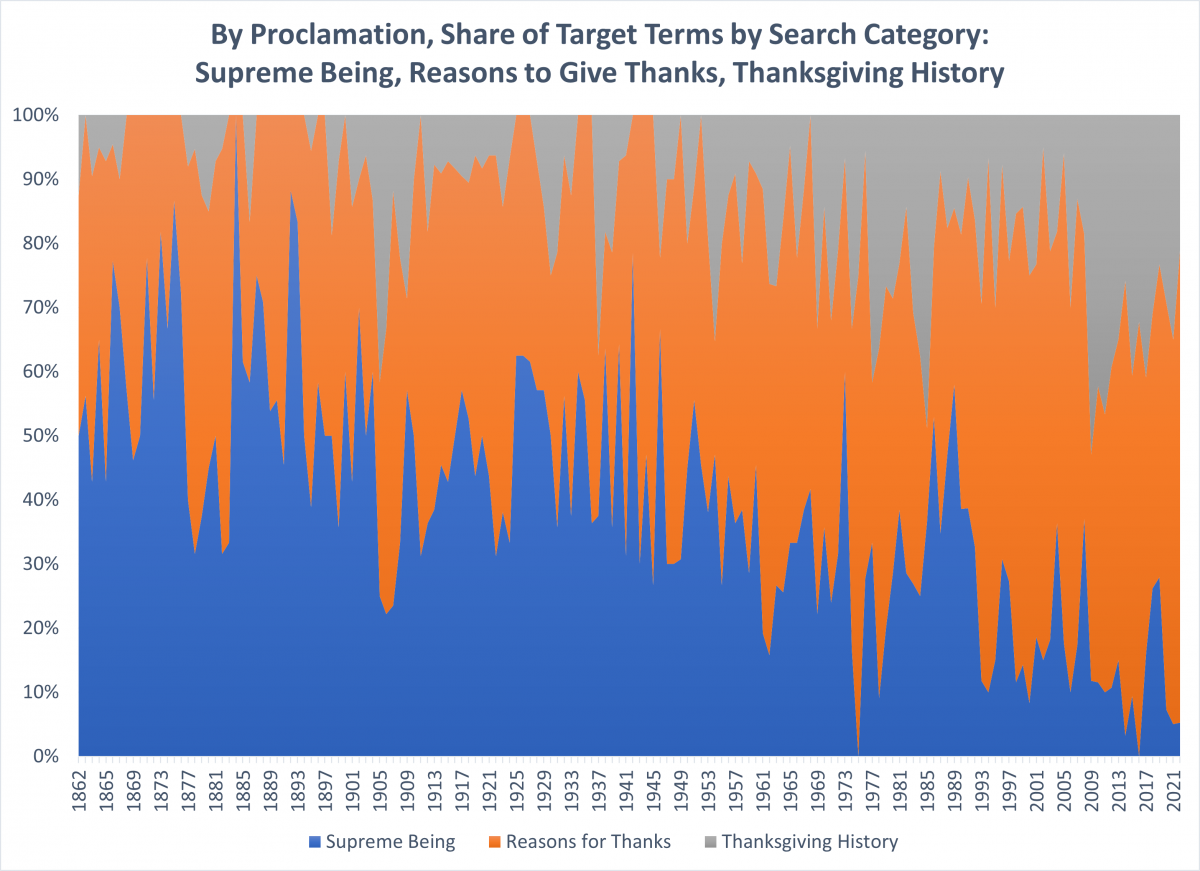

Over the years, however, the Thanksgiving Day Proclamations have increasingly sounded two different and much more secular themes. The first of these involves traces a kind of genealogy of Thanksgiving, back to a “first Thanksgiving” of Plymouth Colony. The other invokes an array of values and ideals that are, at least by implication, distinctively American and provide the motive for our thanks.

Tracking the Themes in the Language of the Proclamations

How have Presidents varied in addressing these questions? To track variation over time, we have looked at the frequency of terms that reflect each of these themes. We have also looked at contrasts between periods that scholars have often treated as defining political eras: Lincoln through Hoover; Franklin D. Roosevelt through Carter; Reagan through the present.

What kind of reference is there to a Supreme Being?

A consistent feature of almost every Thanksgiving Proclamation is at least one reference—sometimes many—to a Supreme Being. Our search in this respect is close to being exhaustive.[2] References to God occur nearly five times on average in every proclamation throughout the study period except two: Ford 1975, and Obama 2016. Both have none. The share of these Supreme Being references in post-1932 proclamations is 55 percent--very close to the proportion of proclamations that were issued post-1932 (i.e., 52 percent).

So the more recent proclamations are, as a generalization, just as reverential as they were in the latter 19th century. However, after 1932, Thanksgiving Proclamations shifted in two ways. First is the emergence of frequent and regular historical references. The second is a more extended articulation of particular values Americans share and benefits for which we should be grateful.

What reference is made to history and customs?

In the post-1932 period, there is a stronger emphasis on American history, especially on references to traditional Thanksgiving observances. These proclamations typically note a long American tradition of "giving thanks" starting with the “original” Thanksgiving of the Plymouth Colony.[3] Seventy-two percent of the specific historical references we counted are from the post-1932 period (vs. 56% of the proclamations). Since 1968, all proclamations have included multiple explicit historical references.

Theodore Roosevelt’s 1908 proclamation was the first to mention Indians--but not in positive terms. Roosevelt pointed out that the first colonies were “hemmed in” by “Indian-haunted wilderness.”

Similarly, in 1971 Nixon invoked the Indian threat to settlers. That proclamation noted that the Pilgrims “level[ed] the earth” above their graves to try to prevent the Indians from learning “how many were suffering.”

The first mention of “native Americans” was by Ford in 1975, who somewhat ambiguously suggests that together with other people they “have come to share in the rewards and responsibilities of our American Republic.”

Ronald Reagan first emphasized the way Indians assisted the Pilgrims in his proclamations of 1981 and 1984. In 1984, Reagan pointed out that there were native traditions of “thanksgiving” that long predated the Pilgrims. Reagan marks an important rhetorical shift.

Ongoing tensions about the history and meaning of Thanksgiving can be traced through explicit references to the Wampanoag tribe. There are important differences in the characterization of the relationship between the Pilgrims and the Indians. The first mention of the tribe by name is in Clinton’s 1995 proclamation. Clinton notes that the Massachusetts Governor, “invited members of the neighboring Wampanoag tribe to join” in a celebration.

The Wampanoag became a constant feature of Thanksgiving proclamations in 2010 but with some significant differences in emphasis. In 2010, Obama noted that the Wampanoag “had been living and thriving around Plymouth . . . for thousands of years.” The skills of these Natives “helped the early colonists survive.” And, he pointed out, the Wampanoag culture continues to be part of our Nation’s heritage.

In a first for Republican presidents, Trump referred to the Wampanoag (not just to “Indians”) in all four of his Thanksgiving proclamations. But the tone was somewhat different from Obama’s. For example, Trump’s 2020 proclamation stresses the bravery and commitment of the Pilgrims who brought “the first seeds of democracy to our land.” The Wampanoag were “their neighbors,” with whom the Pilgrims “forged friendships.” The Pilgrim’s first Thanksgiving celebration was “alongside” the Native neighors. There is no mention of any benefits the Wampanoag provided to the Pilgrims.

From Lincoln through Hoover by our search, there was use of only one of our historical reference terms on average per proclamation. From FDR through Carter, there were 2.4. Throughout the (ongoing) Reagan era, the average has been 7.4.

For what do we give thanks?

For what, specifically, are Americans to give thanks on this holiday? Lincoln sounded one primary theme: gratitude for bounty and prosperity. This has been echoed in two-thirds of all Thanksgiving proclamations. But, of course, the Thanksgiving holiday has been observed in both good times and bad; prosperity and depression. What then?

One of the most common motive themes is peace. Reference to peace (or some variant of the word) occurs in 72 percent of Thanksgiving proclamations.

Over time, Thanksgiving proclamations have pointed to a diverse set of values and qualities in American life for which we should be grateful. Often mentioned have been freedom(s), love, family, liberty, hope, faith, community, care, and justice.[4]

It is perhaps striking how often Presidents have used Thanksgiving proclamations to urge Americans to find joy with family, to assist others, to practice generosity, to express compassion, to share our blessings, to welcome others who are different, or to celebrate national unity. Seventy-eight percent of Proclamations include terms that we think reflect this kind of sentiment.

Equally surprising is how few references there are to anything involving US governmental institutions, democracy, the Constitution, laws, or voting. Even with a very generous search, we find these kind of items in only 22 percent of proclamations. While Thanksgiving itself is distinctively “American,” Presidents have not tried to make it a celebration of our governmental forms.

In only one instance—the 1884 Proclamation of Chester Arthur--did our search come up with no examples of these kinds of “reasons to give thanks.” Arthur’s was a simple call to give thanks to God.

As was the case with the historical references, the “meaning of Thanksgiving references” increased steadily across the three eras. The Lincoln-Hoover era averages 5.8 mentions; FDR through Carter, 7.5; Reagan to Biden 15.2.

Of course, our search cannot possibly capture every single expression of worthy American virtues noted in Thanksgiving Proclamations. Readers may note with interest this excerpt from Theodore Roosevelt’s 1907 Proclamation:

“We should earnestly pray that this spirit of righteousness and justice may grow in the hearts of all of us, and that our souls may be inclined ever more both toward the virtues that tell for gentleness and tenderness, for loving kindness and forbearance, one toward another, and toward those no less necessary virtues that make for manliness and rugged hardihood; for without these qualities neither nation nor individual can rise to the level of greatness.” [emphasis added]

No President has been as taken with the concept of manliness as Theodore Roosevelt.

In short, the “modern” Thanksgiving proclamation is much more than a simple expression of gratitude to a higher power for peace and prosperity. Rather, the modern Thanksgiving proclamation reflects an effort to root the practice in a distinctive American history and to highlight a specific set of ideas about the reasons to be grateful for being an American. This historical trend is illustrated in the graph below, contrasting over time the share of references to a Supreme Being, to Thanksgiving history, and to “reasons to give thanks.”

________________________________________________

Sources:

FDR Library, [nd]. “The Year we had Two Thanksgivings,” http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/thanksg.html

History.com. 2019. “History of Thanksgiving,” https://www.history.com/topics/thanksgiving/history-of-thanksgiving

Library of Congress [nd] “Primary Source Set: Thanksgiving." [Classroom materials] https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/thanksgiving/?loclr=blogtea

Pleck, Elizabeth, 1999. “The Making of the Domestic Occasion: The History of Thanksgiving in the United States.” Journal of Social History 32:4 (Summer): 773-789

United States, National Archives and Records Administration. [nd] “Congress Establishes Thanksgiving.” https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/thanksgiving

Various Authors, 1843. “History of Thanksgiving,” Boston Recorder December 7.

Notes:

[1] In 1865 Andrew Johnson proclaimed the first Thursday in December. Readers may be entertained by applying our "three questions" to the Thanksgiving Day proclamations of Warren G. Harding, whose text was inadvertently omitted from the analysis that follows.

[2] Containing text (observed frequency): All-giver (1), Almighty (152), Creator (14), Divine (69), Father (17), Giver of all good (2), Giver of all things (1), Giver of Every (3), Giver of every good and perfect gift (1), Giver of Good (3), God (382), He (95), Heavenly Source (1), Him (51), His (210), Most High (11), Providence (34), Ruler of Nations (8), Ruler of the Universe (8), Source of all good (1), Supreme Author (1), the Lord (30), Thee (3), Thou (2), Throne of Grace (3), Thy (6)

[3] Containing text (observed frequency): American Revolution (3), ancestors (9), Civil War (28), colonial customs (1), Colony (6), Continental Congress (7), custom (49), Dutch (1), earliest days of our Republic (1), festival (8), first Thanksgiving Day (4), forebears (10), forefather (18), founded (7), frontier colonies (1), George Washington (30), habit (8), heritage (30), history of our country (1), Indian (4), indigenous people (2), Iroquois (3), Lincoln (41), Maine (1), Massachusetts (11), Mayflower (8), native (13), oldest continuously surviving republic (1), original (2), our fathers (8), our history (10), Pilgrim (11), pilgrimage (1), Pilgrims (53), Plymouth (19), President Washington (9), Revolutionary War (3), Sarah Josepha Hale (1), settlers (19), Spaniards (1), tradition (69), tribe (10), Valley Forge (5), Virginia (5), Wampanoag (21), William Bradford (4), years ago (18)

[4] Containing text (observed frequency across 162 proclamations): bountiful (24), bounty (59), brotherhood (7), care (44), character (13), charitable spirit (1), charity (22), community (40), compassion (20), Constitution of the Republic (1), constitutional democracy (1), constitutional government (1), constitutions of government (3), creed (10), cultural pluralism (1), decency (3), democracy (16), different backgrounds and beliefs (1), dignity (8), diverse (4), diversity (6), duty and obligation (1), efforts to empathize (1), elections (1), equal justice (1), equality (8), faith (40), family (74), fraternal feeling (1), free elections (1), free institutions (5), freedom (105), freedoms (25), Freedom from (1), generosity (25), generous nature (1), good will (6), gratitude (155), gratitude and duty (1), harmony (13), health (27), hope (52), humility (20), Judeo-Christian (3), justice (39), laws have been respected (1), laws of the highest morality (1), liberty (67), love (91), moral values (1), obedience to mild laws (1), offering an asylum (1), optimism (2), order has been maintained (1), order is being maintained (1), our Constitution (3), patriotism (5), peace (189), plenty (25), preamble to the Constitution (1), prosperity (67), pursuit of happiness (1), qualities of heart (1), religious faith (1), remembrance of those less fortunate (1), respect and appreciation for our differences (1), respect for law and order (1), righteousness (15), rights (16), rule of law (2), self-determination (1), selflessness (3), share our blessings (2), social order (1), spread of intelligence and learning (1), stability (4), stand strong (1), ties of friendship (3), to vote (1), under the Constitution (2), unity (23), virtuous (1), voting (3), way of life (6), willing to fight (1), wisdom (31), wise institutions (1), wise, just and constitutional laws (1), worth of man (1)