To the Senate of the United States:

Ever since the beginning of the present session of the Senate the different heads of the Departments attached to the executive branch of the Government have been plied with various requests and demands from committees of the Senate, from members of such committees, and at last from the Senate itself, requiring the transmission of reasons for the suspension of certain officials during the recess of that body, or for the papers touching the conduct of such officials, or for all papers and documents relating to such suspensions, or for all documents and papers filed in such Departments in relation to the management and conduct of the offices held by such suspended officials.

The different terms from time to time adopted in making these requests and demands, the order in which they succeeded each other, and the fact that when made by the Senate the resolution for that purpose was passed in executive session have led to the presumption, the correctness of which will, I suppose, be candidly admitted, that from first to last the information thus sought and the papers thus demanded were desired for use by the Senate and its committees in considering the propriety of the suspensions referred to.

Though these suspensions are my executive acts, based upon considerations addressed to me alone and for which I am wholly responsible, I have had no invitation from the Senate to state the position which I have felt constrained to assume in relation to the same or to interpret for myself my acts and motives in the premises.

In this condition of affairs I have forborne addressing the Senate upon the subject, lest I might be accused of thrusting myself unbidden upon the attention of that body.

But the report of the Committee on the Judiciary of the Senate lately presented and published, which censures the Attorney-General of the United States for his refusal to transmit certain papers relating to a suspension from office, and which also, if I correctly interpret it, evinces a misapprehension of the position of the Executive upon the question of such suspensions, will, I hope, justify this communication.

This report is predicated upon a resolution of the Senate directed to the Attorney-General and his reply to the same. This resolution was adopted in executive session devoted entirely to business connected with the consideration of nominations for office. It required the Attorney-General "to transmit to the Senate copies of all documents and papers that have been filed in the Department of Justice since the 1st day of January, 1885, in relation to the management and conduct of the office of district attorney of the United States for the southern district of Alabama."

The incumbent of this office on the 1st day of January, 1885, and until the 17th day of July ensuing, was George M. Duskin, who on the day last mentioned was suspended by an Executive order, and John D. Burnett designated to perform the duties of said office. At the time of the passage of the resolution above referred to the nomination of Burnett for said office was pending before the Senate, and all the papers relating to said nomination were before that body for its inspection and information.

In reply to this resolution the Attorney-General, after referring to the fact that the papers relating to the nomination of Burnett had already been sent to the Senate, stated that he was directed by the President to say that--

The papers and documents which are mentioned in said resolution and still remaining in the custody of this Department, having exclusive reference to the suspension by the President of George M. Duskin, the late incumbent of the office of district attorney for the southern district of Alabama, it is not considered that the public interests will be promoted by a compliance with said resolution and the transmission of the papers and documents therein mentioned to the Senate in executive session.

Upon this resolution and the answer thereto the issue is thus stated by the Committee on the Judiciary at the outset of the report:

The important question, then, is whether it is within the constitutional competence of either House of Congress to have access to the official papers and documents in the various public offices of the United States created by laws enacted by themselves.

I do not suppose that "the public offices of the United States" are regulated or controlled in their relations to either House of Congress by the fact that they were "created by laws enacted by themselves." It must be that these instrumentalities were created for the benefit of the people and to answer the general purposes of government under the Constitution and the laws, and that they are unencumbered by any lien in favor of either branch of Congress growing out of their construction, and unembarrassed by any obligation to the Senate as the price of their creation.

The complaint of the committee that access to official papers in the public offices is denied the Senate is met by the statement that at no time has it been the disposition or the intention of the President or any Department of the executive branch of the Government to withhold from the Senate official documents or papers filed in any of the public offices. While it is by no means conceded that the Senate has the right in any case to review the act of the Executive in removing or suspending a public officer, upon official documents or otherwise, it is considered that documents and papers of that nature should, because they are official, be freely transmitted to the Senate upon its demand, trusting the use of the same for proper and legitimate purposes to the good faith of that body; and though no such paper or document has been specifically demanded in any of the numerous requests and demands made upon the Departments, yet as often as they were found in the public offices they have been furnished in answer to such applications.

The letter of the Attorney-General in response to the resolution of the Senate in the particular case mentioned in the committee's report was written at my suggestion and by my direction. There had been no official papers or documents filed in his Department relating to the case within the period specified in the resolution. The letter was intended, by its description of the papers and documents remaining in the custody of the Department, to convey the idea that they were not official; and it was assumed that the resolution called for information, papers, and documents of the same character as were required by the requests and demands which preceded it.

Everything that had been written or done on behalf of the Senate from the beginning pointed to all letters and papers of a private and unofficial nature as the objects of search, if they were to be found in the Departments, and provided they had been presented to the Executive with a view to their consideration upon the question of suspension from office.

Against the transmission of such papers and documents I have interposed my advice and direction. This has not been done, as is suggested in the committee's report, upon the assumption on my part that the Attorney-General or any other head of a Department "is the servant of the President, and is to give or withhold copies of documents in his office according to the will of the Executive and not otherwise," but because I regard the papers and documents withheld and addressed to me or intended for my use and action purely unofficial and private, not infrequently confidential, and having reference to the performance of a duty exclusively mine. I consider them in no proper sense as upon the files of the Department, but as deposited there for my convenience, remaining still completely under my control. I suppose if I desired to take them into my custody I might do so with entire propriety, and if I saw fit to destroy them no one could complain.

Even the committee in its report appears to concede that there may be with the President or in the Departments papers and documents which, on account of their unofficial character, are not subject to the inspection of the Congress. A reference in the report to instances where the House of Representatives ought not to succeed in a call for the production of papers is immediately followed by this statement:

The committee feels authorized to state, after a somewhat careful research, that within the foregoing limits there is scarcely in the history of this Government, until now, any instance of a refusal by a head of a Department, or even of the President himself, to communicate official facts and information, as distinguished from private and unofficial papers, motions, views, reasons, and opinions, to either House of Congress when unconditionally demanded.

To which of the classes thus recognized do the papers and documents belong that are now the objects of the Senate's quest?

They consist of letters and representations addressed to the Executive or intended for his inspection; they are voluntarily written and presented by private citizens who are not in the least instigated thereto by any official invitation or at all subject to official control. While some of them are entitled to Executive consideration, many of them are so irrelevant, or in the light of other facts so worthless, that they have not been given the least weight in determining the question to which they are supposed to relate.

Are all these, simply because they are preserved, to be considered official documents and subject to the inspection of the Senate? If not, who is to determine which belong to this class? Are the motives and purposes of the Senate, as they are day by day developed, such as would be satisfied with my selection? Am I to submit to theirs at the risk of being charged with making a suspension from office upon evidence which was not even considered?

Are these papers to be regarded official because they have not only been presented but preserved in the public offices?

Their nature and character remain the same whether they are kept in the Executive Mansion or deposited in the Departments. There is no mysterious power of transmutation in departmental custody, nor is there magic in the undefined and sacred solemnity of Department files. If the presence of these papers in the public offices is a stumbling block in the way of the performance of Senatorial duty, it can be easily removed.

The papers and documents which have been described derive no official character from any constitutional, statutory, or other requirement making them necessary to the performance of the official duty of the Executive.

It will not be denied, I suppose, that the President may suspend a public officer in the entire absence of any papers or documents to aid his official judgment and discretion; and I am quite prepared to avow that the cases are not few in which suspensions from office have depended more upon oral representations made to me by citizens of known good repute and by members of the House of Representatives and Senators of the United States than upon any letters and documents presented for my examination. I have not felt justified in suspecting the veracity, integrity, and patriotism of Senators, or ignoring their representations, because they were not in party affiliation with the majority of their associates; and I recall a few suspensions which bear the approval of individual members identified politically with the majority in the Senate.

While, therefore, I am constrained to deny the right of the Senate to the papers and documents described, so far as the right to the same is based upon the claim that they are in any view of the subject official, I am also led unequivocally to dispute the right of the Senate by the aid of any documents whatever, or in any way save through the judicial process of trial on impeachment, to review or reverse the acts of the Executive in the suspension, during the recess of the Senate, of Federal officials.

I believe the power to remove or suspend such officials is vested in the President alone by the Constitution, which in express terms provides that "the executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America," and that "he shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed."

The Senate belongs to the legislative branch of the Government. When the Constitution by express provision superadded to its legislative duties the right to advise and consent to appointments to office and to sit as a court of impeachment, it conferred upon that body all the control and regulation of Executive action supposed to be necessary for the safety of the people; and this express and special grant of such extraordinary powers, not in any way related to or growing out of general Senatorial duty, and in itself a departure from the general plan of our Government, should be held, under a familiar maxim of construction, to exclude every other right of interference with Executive functions.

In the first Congress which assembled after the adoption of the Constitution, comprising many who aided in its preparation, a legislative construction was given to that instrument in which the independence of the Executive in the matter of removals from office was fully sustained.

I think it will be found that in the subsequent discussions of this question there was generally, if not at all times, a proposition pending to in some way curtail this power of the President by legislation, which furnishes evidence that to limit such power it was supposed to be necessary to supplement the Constitution by such legislation.

The first enactment of this description was passed under a stress of partisanship and political bitterness which culminated in the President's impeachment.

This law provided that the Federal officers to which it applied could only be suspended during the recess of the Senate when shown by evidence satisfactory to the President to be guilty of misconduct in office, or crime, or when incapable or disqualified to perform their duties, and that within twenty days after the next meeting of the Senate it should be the duty of the President "to report to the Senate such suspension, with the evidence and reasons for his action in the case."

This statute, passed in 1867, when Congress was overwhelmingly and bitterly opposed politically to the President, may be regarded as an indication that even then it was thought necessary by a Congress determined upon the subjugation of the Executive to legislative will to furnish itself a law for that purpose, instead of attempting to reach the object intended by an invocation of any pretended constitutional right.

The law which thus found its way to our statute book was plain in its terms, and its intent needed no avowal. If valid and now in operation, it would justify the present course of the Senate and command the obedience of the Executive to its demands. It may, however, be remarked in passing that under this law the President had the privilege of presenting to the body which assumed to review his executive acts his reasons therefor, instead of being excluded from explanation or judged by papers found in the Departments.

Two years after the law of 1867 was passed, and within less than five weeks after the inauguration of a President in political accord with both branches of Congress, the sections of the act regulating suspensions from office during the recess of the Senate were entirely repealed, and in their place were substituted provisions which, instead of limiting the causes of suspension to misconduct, crime, disability, or disqualification, expressly permitted such suspension by the President "in his discretion," and completely abandoned the requirement obliging him to report to the Senate "the evidence and reasons" for his action.

With these modifications and with all branches of the Government in political harmony, and in the absence of partisan incentive to captious obstruction, the law as it was left by the amendment of 1869 was much less destructive of Executive discretion. And yet the great general and patriotic citizen who on the 4th day of March, 1869, assumed the duties of Chief Executive, and for whose freer administration of his high office the most hateful restraints of the law of 1867 were, on the 5th day of April, 1869, removed, mindful of his obligation to defend and protect every prerogative of his great trust, and apprehensive of the injury threatened the public service in the continued operation of these stautes even in their modified form, in his first message to Congress advised their repeal and set forth their unconstitutional character and hurtful tendency in the following language:

It may be well to mention here the embarrassment possible to arise from leaving on the statute books the so-called "tenure-of-office acts," and to earnestly recommend their total repeal. It could not have been the intention of the framers of the Constitution, when providing that appointments made by the President should receive the consent of the Senate, that the latter should have the power to retain in office persons placed there by Federal appointment against the will of the President. The law is inconsistent with a faithful and efficient administration of the Government. What faith can an Executive put in officials forced upon him, and those, too, whom he has suspended for reason? How will such officials be likely to serve an Administration which they know does not trust them?

I am unable to state whether or not this recommendation for a repeal of these laws has been since repeated. If it has not, the reason can probably be found in the experience which demonstrated the fact that the necessities of the political situation but rarely developed their vicious character.

And so it happens that after an existence of nearly twenty years of almost innocuous desuetude these laws are brought forth--apparently the repealed as well as the unrepealed--and put in the way of an Executive who is willing, if permitted, to attempt an improvement in the methods of administration.

The constitutionality of these laws is by no means admitted. But why should the provisions of the repealed law, which required specific cause for suspension and a report to the Senate of "evidence and reasons," be now in effect applied to the present Executive, instead of the law, afterwards passed and unrepealed, which distinctly permits suspensions by the President "in his discretion" and carefully omits the requirement that "evidence and reasons for his action in the case" shall be reported to the Senate.

The requests and demands which by the score have for nearly three months been presented to the different Departments of the Government, whatever may be their form, have but one complexion. They assume the right of the Senate to sit in judgment upon the exercise of my exclusive discretion and Executive function, for which I am solely responsible to the people from whom I have so lately received the sacred trust of office. My oath to support and defend the Constitution, my duty to the people who have chosen me to execute the powers of their great office and not to relinquish them, and my duty to the Chief Magistracy, which I must preserve unimpaired in all its dignity and vigor, compel me to refuse compliance with these demands.

To the end that the service may be improved, the Senate is invited to the fullest scrutiny of the persons submitted to them for public office, in recognition of the constitutional power of that body to advise and consent to their appointment. I shall continue, as I have thus far done, to furnish, at the request of the confirming body, all the information I possess touching the fitness of the nominees placed before them for their action, both when they are proposed to fill vacancies and to take the place of suspended officials. Upon a refusal to confirm I shall not assume the right to ask the reasons for the action of the Senate nor question its determination. I can not think that anything more is required to secure worthy incumbents in public office than a careful and independent discharge of our respective duties within their well-defined limits.

Though the propriety of suspensions might be better assured if the action of the President was subject to review by the Senate, yet if the Constitution and the laws have placed this responsibility upon the executive branch of the Government it should not be divided nor the discretion which it involves relinquished.

It has been claimed that the present Executive having pledged himself not to remove officials except for cause, the fact of their suspension implies such misconduct on the part of a suspended official as injures his character and reputation, and therefore the Senate should review the case for his vindication.

I have said that certain officials should not, in my opinion, be removed during the continuance of the term for which they were appointed solely for the purpose of putting in their place those in political affiliation with the appointing power, and this declaration was immediately followed by a description of official partisanship which ought not to entitle those in whom it was exhibited to consideration. It is not apparent how an adherence to the course thus announced carries with it the consequences described. If in any degree the suggestion is worthy of consideration, it is to be hoped that there may be a defense against unjust suspension in the justice of the Executive.

Every pledge which I have made by which I have placed a limitation upon my exercise of executive power has been faithfully redeemed. Of course the pretense is not put forth that no mistakes have been committed; but not a suspension has been made except it appeared to my satisfaction that the public welfare would be improved thereby. Many applications for suspension have been denied, and the adherence to the rule laid down to govern my action as to such suspensions has caused much irritation and impatience on the part of those who have insisted upon more changes in the offices.

The pledges I have made were made to the people, and to them I am responsible for the manner in which they have been redeemed. I am not responsible to the Senate, and I am unwilling to submit my actions and official conduct to them for judgment.

There are no grounds for an allegation that the fear of being found false to my professions influences me in declining to submit to the demands of the Senate. I have not constantly refused to suspend officials, and thus incurred the displeasure of political friends, and yet willfully broken faith with the people for the sake of being false to them.

Neither the discontent of party friends, nor the allurements constantly offered of confirmations of appointees conditioned upon the avowal that suspensions have been made on party grounds alone, nor the threat proposed in the resolutions now before the Senate that no confirmations will be made unless the demands of that body be complied with, are sufficient to discourage or deter me from following in the way which I am convinced leads to better government for the people.

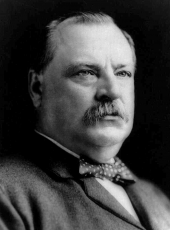

GROVER CLEVELAND

Grover Cleveland, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/204972