To the Senate of the United States.

In compliance with the resolution of the Senate of the 12th instant, I transmit a report of the Secretary of State, with the papers therein referred to, which, with those accompanying the special message this day sent to Congress, are believed to contain all the information requested. The papers relative to the letter of the late minister of France have been added to those called for, that the subject may be fully understood.

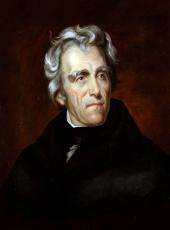

ANDREW JACKSON

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

Washington, January 13, 1836 .

The PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES:

The Secretary of State has the honor to lay before the President a copy of a report made to him in June last, and of a letter addressed to this Department by the late minister of the Government of France, with the correspondence connected with that communication, which, together with a late correspondence between the Secretary of State and the French charge d'affaires and a recent correspondence between the charge d'affaires of the United States at Paris and the Duke de Broglie, already transmitted to the President to be communicated to Congress with his special message relative thereto, are the only papers in the Department of State supposed to be called for by the resolutions of the Senate of the 12th instant.

It will be seen by the correspondence with the charge d'affaires of France that a dispatch to him from the Duke de Broglie was read to the Secretary at the Department in September last. It concluded with an authority to permit a copy to be taken if it was desired. That dispatch being an argumentative answer to the last letter of Mr. Livingston to the French Government, and in affirmance of the right of France to expect explanations of the message of the President, which France had been distinctly and timely informed could not be given without a disregard by the Chief Magistrate of his constitutional obligations, no desire was expressed to obtain a copy, it being obviously improper to receive an argument in a form which admitted of no reply, and necessarily unavailing to inquire how much or how little would satisfy France, when her right to any such explanation had been beforehand so distinctly and formally denied.

All which is respectfully submitted.

JOHN FORSYTH.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

Washington , June 18, 1835.

The PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES:

I have the honor to present, for the examination of the President, three letters received at the Department from _________, dated at Paris, the 19th, 23d, and 30th of April. The last two I found here on my recent return from Georgia. They were received on the 9th and 10th of June; the last came to my own hand yesterday. Several communications have been previously received from the same quarter, all of them volunteered; none of them have been acknowledged. The unsolicited communications to the Department by citizens of the United States of facts that may come to their knowledge while residing abroad, likely to be interesting to their country, are always received with pleasure and carefully preserved on the files of the Government. Even opinions on foreign topics are received with proper respect for the motives and character of those who may choose to express them.

But holding it both improper and dangerous to countenance any of our citizens occupying no public station in sending confidential communications on our affairs with a foreign government at which we have an accredited agent, upon subjects involving the honor of the country, without the knowledge of such agent, and virtually substituting himself as the channel of communication between that government and his own, I considered it my duty to invite Mr. Pageot to the Department to apprise him of the contents of Mr.______'s letter of the 23d of April, and at the same time to inform him that he might communicate the fact to the Duke de Broglie that no notice could be taken of Mr.__________ and his communications.

The extreme and culpable indiscretion of Mr.___________ in this transaction was strikingly illustrated by a remark of Mr. Pageot, after a careful examination of the letter of 23d April, that although without instructions from his Government he would venture to assure me that the Duke de Broglie could not have expected Mr.____________ to make such a communication to the Secretary of State. Declining to enter into the consideration of what the Duke might have expected or intended, I was satisfied with the assurances Mr. Pageot gave me that he would immediately state what had occurred to his Government.

All which is respectfully submitted, with the hope, if the course pursued is approved by the President, that this report may be filed in this Department with the letters to which it refers.

JOHN FORSYTH.

Mr. Forsyth to Mr. Livingston.

No. 50.

(Extract.)

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

Washington, March 5, 1835.

EDWARD LIVINGSTON, ESQ.,

Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, Paris.

SIR: In my note No. 49 you were informed that the last letter of M. Serurier would be made the subject of separate and particular instructions to you. Unwilling to add to the irritation produced by recent incidents in our relations with France, the President will not take for granted that the very exceptionable language of the French minister was used by the orders or will be countenanced by the authority of the King of France. You will therefore, as early as practicable after this reaches you, call the attention of the minister of foreign affairs to the following passage in M. Serurier's letter:

"Les plaintes que porte M. le President conere le pretendu non-accomplissement des engagemens pris par le Gouvernement du Roi a la suite du vote du 1er avril 1834, ne sont pas seulement etrange par l'entiere inexactitude des allegations sur lesquelles elles reposent, mats aussi parceque les explications qu'a recues a Paris M. Livingston, et celles que le soussigne a donnees directement an cabinet de Washington semblaient ne pas laisser meme la possibilite d'un malentendu sur des points aussi delicats."

In all discussions between government and government, whatever may be the differences of opinion on the facts or principles brought into view, the invariable rule of courtesy and justice demands that the sincerity of the opposing party in the views which it entertains should never be called in question. Facts may be denied deductions examined, disproved, and condemned, without just cause of offense; but no impeachment of the integrity of the Government in its reliance on the correctness of its own views can be permitted without a total forgetfulness of self-respect. In the sentence quoted from M. Serurier's letter no exception is taken to the assertion that the complaints of this Government are founded upon allegations entirely inexact, nor upon that which declares the explanations given here or in Paris appeared not to have left even the possibility of a misunderstanding on such delicate points. The correctness of these assertions we shall always dispute, and while the records of the two Governments endure we shall find no difficulty in shewing that they are groundless; but when M. Serurier chooses to qualify the nonaccomplishment of the engagements made by France, to which the President refers, as a pretended non-accomplishment, he conveys the idea that the Chief Magistrate knows or believes that he is in error, and acting upon this known error seeks to impose it upon Congress and the world as truth. In this sense it is a direct attack upon the integrity of the Chief Magistrate of the Republic. As such it must be indignantly repelled; and it being a question of moral delinquency between the two Governments, the evidence against France, by whom it is raised, must be sternly arrayed. You will ascertain, therefore, if it has been used by the authority or receives the sanction of the Government of France in that sense. Should it be disavowed or explained, as from the note of the Count de Rigny to you, written at the moment of great excitement, and in its matter not differing from M. Serurier's, it is presumed it will be, you will then use the materials herewith communicated, or already in your power, in a temper of great forbearance, but with a firmness of tone not to be mistaken, to answer the substance of the note itself.

Mr. Serurier to Mr. Forsyth.

(Translation.)

WASHINGTON, February 23, 1835.

Hon. JOHN FORSYTH,

Secretary of State.

The undersigned, envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary of His Majesty the King of the French at Washington, has received orders to present the following note to the Secretary of State of the Government of the United States:

It would be superfluous to say that the message addressed on the 1st of December, 1834, to the Congress of the United States by President Jackson was received at Paris with a sentiment of painful surprise.

The King's Government is far from supposing that the measures recommended in this message to the attention of Congress can be adopted (votees) by that assembly; but even considering the document in question as a mere manifestation of the opinion which the President wishes to express with regard to the course taken in this affair, it is impossible not to consider its publication as a fact of a most serious nature.

The complaints brought forward by the President on account of the pretended nonfulfillment of the engagements entered into by the King's Government after the vote of the 1st of April are strange, not only from the total inaccuracy of the allegations on which they are based, but also because the explanations received by Mr. Livingston at Paris and those which the undersigned has given directly to the Cabinet of Washington seemed not to leave the slightest possibility of misunderstanding on points so delicate.

It appeared, indeed, from these explanations that although the session of the French Chambers, which was opened on the 31st of July last in compliance with an express provision of the charter, was prorogued at the end of a fortnight, before the bill relative to the American claims, announced in the discourse from the throne, could be placed under discussion, this prorogation arose (tendit) entirely from the absolute impossibility of commencing at so premature a period the legislative labors belonging to the year 1835.

It also appeared that the motives which had hindered the formal presentation to the Chambers of the bill in question during the first space of a fortnight originated chiefly in the desire more effectually to secure the success of this important affair by choosing the most opportune moment of offering it to the deliberations of the deputies newly elected, who, perhaps, might have been unfavorably impressed by this unusual haste in submitting it to them so long before the period at which they could enter upon an examination of it.

The undersigned will add that it is, moreover, difficult to comprehend what advantage could have resulted from such a measure, since it could not evidently have produced the effect which the President declares that he had in view, of enabling him to state at the opening of Congress that these long-pending negotiations were definitively closed. The President supposes, it is true, that the Chambers might have been called together anew before the last month of 1834; but even though the session had been opened some months earlier--which for several reasons would have been impossible--the simplest calculation will serve to shew that in no case could the decision of the Chambers have been taken, much less made known at Washington, before the 1st of December.

The King's Government had a right (devait) to believe that considerations so striking would have proved convincing with the Cabinet of the United States, and the more so as no direct communication made to the undersigned by this Cabinet or transmitted at Paris by Mr. Livingston had given token of the irritation and misunderstandings which the message of December 1 has thus deplorably revealed: and as Mr. Livingston, with that judicious spirit which characterizes him, coinciding with the system of (menagemens) precautions and temporizing prudence adopted by the cabinet of the Tuileries with a view to the common interests, had even requested at the moment of the meeting of the Chambers that the presentation of the bill in question might be deferred, in order that its discussion should not be mingled with debates of another nature, with which its coincidence might place it in jeopardy.

This last obstacle had just been removed and the bill was about to be presented to the Chamber of Deputies when the arrival of the message, by creating in the minds of all a degree of astonishment at least equal to the just irritation which it could not fail to produce, has forced the Government of the King to deliberate on the part which it had to adopt.

Strong in its own right and dignity, it did not conceive that the inexplicable act of the President ought to cause it to renounce absolutely a determination the origin of which had been its respect for engagements (loyaute) and its good feelings toward a friendly nation. Although it does not conceal from itself that the provocation given at Washington has materially increased the difficulties of the case, already so great, yet it has determined to ask from the Chambers an appropriation of twenty-five millions to meet the engagements of the treaty of July 4.

But His Majesty has at the same time resolved no longer to expose his minister to hear such language as that held on December 1. The undersigned has received orders to return to France, and the dispatch of this order has been made known to Mr. Livingston.

The undersigned has the honor to present to the Secretary of State the assurance of his high consideration.

SERURIER.

Mr. Livingston to the Duke de Broglie.

LEGATION OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Paris, April 18, 1835.

M. LE DUC: I am specially directed to call the attention of His Majesty's Government to the following passage in the note presented by M. Serurier to the Secretary of State at Washington:

"Les plaintes que porte Monsieur le President contre le pretendu non-accomplissement des engagemens pris par le Gouvernement du Roi a la suite du vote du 1er avril 1834, ne sont pus seulement etrange par l'entiere inexactitude des allegations sur lesquelles elles reposent, mais aussi parceque les explications qu'a recues a Paris M. Livingston, et celles que le soussigne a donnees directement an cabinet de Washington, semblaient ne pus laisser meme la possibilite d'un malentendu sur des points aussi delicats."

Each party in a discussion of this nature has an uncontested right to make its own statement of facts and draw its own conclusions from them, to acknowledge or deny the accuracy of counter proof or the force of objecting arguments, with no other restraints than those which respect for his own convictions, the opinion of the world, and the rules of common courtesy impose. This freedom of argument is essential to the discussion of all national concerns, and can not be objected to without showing an improper and irritating susceptibility. It is for this reason that the Government of the United States make no complaint of the assertion in the note presented by M. Serurier that the statement of facts contained in the President's message is inaccurate, and that the causes assigned for the delay in presenting the law ought to have satisfied them. On their part they contest the facts, deny the accuracy of the conclusions, and appeal to the record, to reason, and to the sense of justice Of His Majesty's Government on a more mature consideration of the case for their justification. But I am further instructed to say that there is one expression in the passage I have quoted which in one signification could not be admitted even within the broad limits which are allowed to discussions of this nature, and which, therefore, the President will not believe to have been used in the offensive sense that might be attributed to it. The word "pretendu" sometimes, it is believed, in French, and its translation always in English, implies not only that the assertion which it qualifies is untrue, but that the party making it knows it to be so and uses it for the purposes of deception.

Although the President can not believe that the term was employed in this injurious sense, yet the bare possibility of a construction being put upon it which it would be incumbent on him to repel with indignation obliges him to ask for the necessary explanation.

I have the honor to be, etc.,

EDWARD LIVINGSTON.

Mr. Livingston to Mr. Forsyth.

(Extract.)

WASHINGTON, June 29, 1835 .

* * * Having received my passports, I left Paris on the 29th of April. At the time of my departure the note, of which a copy has been transmitted to you, asking an explanation of the terms used in M. Serurier's communication to the Department, remained unanswered, but I have reason to believe that the answer when given will be satisfactory.

Andrew Jackson, Special Message Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/200720